Despite Prevalent Trauma, From School Shootings to the Opioid Epidemic, Few States Have Policies to Fully Address Student Needs, Study Finds

This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new research and data. Go Deeper: See our full series.

Despite the pervasive effect of stressful experiences — from mass school shootings to the opioid epidemic — on student performance, only 11 states encourage or require staff training on the effects of trauma. Half of states have policies on suicide prevention. And just one state, Vermont, requires a school nurse to be available daily at every school campus.

Those are among the key findings of a report released Thursday by the nonprofit Child Trends, which found that most states have failed to adopt a comprehensive set of policies to address student well-being.

Nearly half of America’s students have traumatic experiences, including divorce, substance abuse, and domestic violence, according to the Child Trends report, leading an increasing number of states to enact laws that aim to better equip schools to educate youth who experience trauma. But Child Trends researchers argue that a more comprehensive, “whole child” approach is key. Such an approach, which focuses on a range of factors from student health to school safety, is necessary because disparate school policies affect student welfare, said Kristen Harper, Child Trends’s director for policy development. Even as districts implement strategies to help students with adverse experiences, the report argues that other school policies, such as frequent suspensions, could further traumatize youth.

“You could take a child that may need mental health services, for example, and get them those services,” Harper said in an interview with The 74. “But if the child’s behavior in the classroom still means that they’re getting suspended or they’re the target of corporal punishment or seclusion and restraint, that’s still a scenario where we’re taking a child that’s experienced trauma and adding trauma on top of it.”

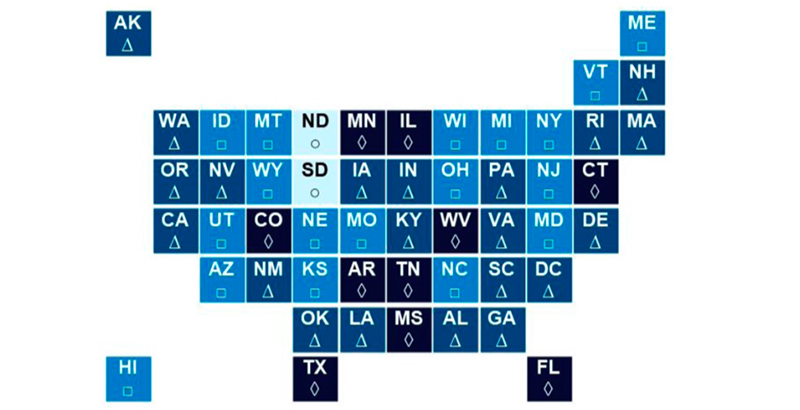

The report focuses on state policies addressing a wide range of factors that contribute to healthy school environments. Researchers utilized a framework created in 2013 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which identifies 10 key components. Among them are health education, nutrition services, counseling, schools’ physical environments, employee wellness, and family engagement. Laws in 10 states offered “deep coverage” of the framework, Child Trends found, with comprehensive policies on at least six of the policy areas. The bulk of states had less comprehensive policies on the range of issues, but two states in particular — South Dakota and North Dakota — had “weak” coverage of the policy areas.

Though most states lack laws focused on student trauma, Child Trends found such policies to be an emerging trend. Last year, at least seven states passed legislation to address students with traumatic stress. Meanwhile, other factors have received less attention from policymakers, including those that focus on stress or substance abuse among employees.

Policies in only two states, Mississippi and Rhode Island, touch on employee wellness “in more than just an artificial way,” said Deborah Temkin, Child Trends’s senior program area director for education. Temkin theorized that states infrequently address employee wellness because education policy generally centers on improving student academic outcomes “and not that broader community.”

Temkin said that while each of the factors contributes to positive school environments in different ways, they’re all interrelated. But policymakers, however, tend to address them in silos, often in response to a crisis. For example, states rushed to adopt new bullying laws several years ago after a series of youth suicides were blamed on harassment. She said this approach often fails to address the way in which multiple issues — like policies around school discipline and social and emotional learning — interact. A recent example of how policies intersect emerged after multiple mass school shootings last year. In order to ensure campuses are safe, some advocates argued, schools need to better address students’ mental health needs.

“That is really driving toward this idea that, in order for these policies to really be effective, they need to be better integrated,” Temkin said.

Unsurprisingly, state policy tends to be geographically specific. For example, Mississippi policies addressing physical education are among the nation’s most comprehensive. Mississippi also has the country’s highest childhood obesity rate.

As the Child Trends reports encourage policymakers to analyze a wide range of policies to address the needs of students, researchers caution that merely having regulations on the books doesn’t necessarily mean they are being implemented effectively. That’s an issue researchers aim to tackle in a forthcoming report.

“We don’t necessarily have the evidence to say that putting a policy in place at the state level necessarily benefits outcomes,” Temkin said. “It’s something that a lot of people theorize and expect to happen, but it’s still very much an empirical question at this point: What level of policymaking is really necessary to make these changes happen?”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)