The Every Student Succeeds Act was supposed to change everything in the often-rancorous world of K-12 education. The law, which President Obama called an “early Christmas present” for America’s students and teachers, ushered in an era of peace. The overarching theme of the bill? Return the authority over schools and classrooms that had been vested with officials in Washington, D.C., to state legislatures and local school boards.

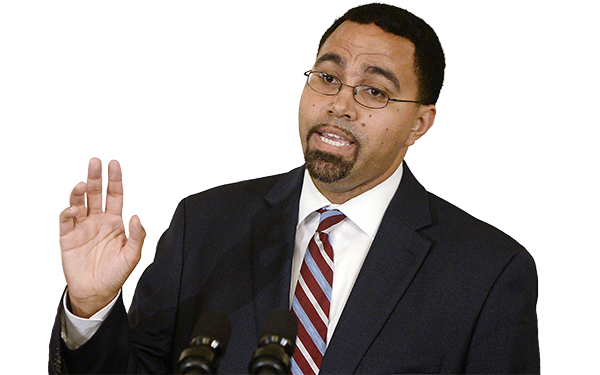

Someone forgot to tell Education Secretary John King.

Five months after the hard-fought compromise became law, the department put forth a proposal aimed at remediating spending disparities between poor and wealthy students. The “supplement not supplant” proposal under the $15 billion Title 1 program is part of a larger Obama administration emphasis on civil rights and equity in education.

“Supplement not supplant” requires districts to show they are using federal Title I funds for poor children in addition to — rather than instead of — the dollars that state and local governments should already being spending on schools. Districts have to show they’re spending roughly the same per student at the poorest schools as the average being spent at wealthier ones.

The Education Department for the first time wants districts to include teacher salaries in that spending calculation — potentially a big difference, given that newer teachers with lower salaries often end up teaching students in poverty at greater rates than their more experienced and better-paid colleagues. Unions fear that such a regulation could require the transfer of better-paid, more experienced teachers from wealthier schools to poorer ones, which could violate seniority or collective bargaining agreements.

The backlash was strong and swift. Negotiators representing teachers unions, state education secretaries, local school boards and others refused to sign off on the language. Republicans — in particular Sen. Lamar Alexander, who chairs the Education Committee — say the change violates not only the spirit, but the letter of the Every Student Succeeds Act, as judged by the nonpartisan Congressional Research Service.

“The administration may get an A for cleverness, but an F for following the law,” Alexander said at a May 18 hearing.

Despite the backlash, King and other education department officials continue to defend the proposal.

King at first argued technicalities, but has pivoted to take a harder line. He’s made it clear that he sees strong enforcement on school spending as his duty to uphold the administration’s legacy on education reform and civil rights.

On May 17, the 62nd anniversary of the landmark Brown v. Board of Education school desegregation ruling, King drew a direct line between the civil rights legacy of that case, ESSA, and the “supplement not supplant” regulations.

“It is both our responsibility and moral obligation to build on the civil rights legacy of [the original federal K-12 education law from the 1960s] and ensure Title I dollars are truly supplemental,” King said, according to a transcript released by the department. “Without meaningful enforcement, high-poverty, high-need schools lose resources to which they are entitled and generations of students lose opportunities they deserve.”

Other education department officials have echoed that sentiment elsewhere.

Dollars, and how they’re spent in schools, count, Ary Amerikaner, a deputy assistant secretary, told the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights.

“Dollars matter because you can buy a lot of different kinds of things with dollars. You can buy more teachers, you can buy often more experienced teachers,” she said at the commission’s May 20 briefing on public education funding inequality. “It’s important that any calculation that is based on dollars, that it includes all of the dollars in the system.”

The latest actions on “supplement not supplant” can’t be taken in isolation, either from previous department efforts or larger Obama administration goals.

Congressional Republicans have been displeased with other department enforcement initiatives over the last eight years — think placing strenuous conditions on states in exchange for No Child Left Behind waivers, or the recent guidance that transgendered students be allowed to use the bathroom of the gender with which they identify. (Alexander and other Republicans went so far as to publicly contradict the administration’s ability to regulate the latter issue. “Until Congress or the courts settle the federal law, states and school districts are free to devise their own reasonable solutions,” they wrote in a letter to King and Attorney General Loretta Lynch.)

They’re also a part of the president’s push to accomplish as much as possible in the time he has left using “pen and phone” — either by administrative regulations, executive orders or the power of the bully pulpit. Some of those edicts, like immigration enforcement or gun control, have been true flashpoints for Republicans and eventually the subject of lawsuits.

Although civil rights groups and many congressional Democrats back the department’s proposal, some have already raised the specter of an education system once again plunged into continual fighting.

“What worries me is that if we get into a wrangle over this regulation…then we’re going to start getting distracted from all the areas we baked into this law where there is common agreement,” Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, Democrat of Rhode Island, said at the May 18 hearing. “I don’t want to end up in a situation where nobody will agree to any regulation of (ESSA) because people are wading back to be against anything and everything, no matter what it is.”

The education department couldn’t get agreement from negotiators working on ESSA rulemaking, so are “considering exactly how to move forward,” King said. “But we start from what I think is a pretty simple assumption: if Title I schools are being systematically shortchanged before federal dollars arrive, then those dollars are not truly supplemental.”

The clock is ticking on King’s tenure, along with Obama’s. The department can now write the regulation as officials see fit and issue it through the standard rulemaking process, which invites public comment after publication. Those suggestions might or might not be included in the final version; lawsuits by aggrieved school districts or congressional efforts to block the rules would come after they’re published.

King seems poised for that showdown.

“One of the federal government’s historic roles has been to protect our most vulnerable students,” King said last week. “I take very seriously our obligation to ensure that the supplement, not supplant requirement is implemented in a way that does just that — protects the needs of students and teachers working in high poverty schools.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)