School districts across the country have dramatically altered how they deal with student misbehavior. From Los Angeles to Chicago to New York City, schools have reduced the frequency with which they give out-of-school suspensions, saying taking students out of the classroom does more harm than good.

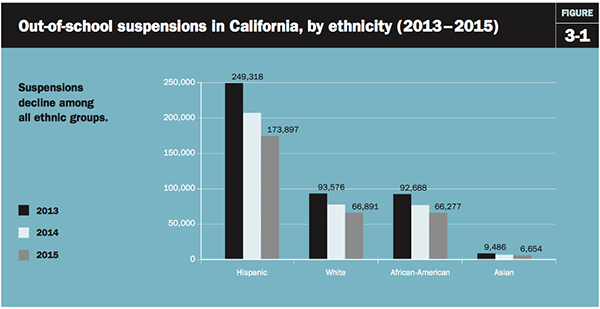

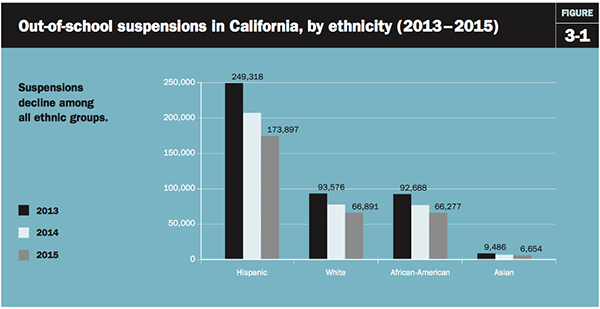

A recent analysis of California schools found that suspensions there declined precipitously across all ethnic groups between 2013 and 2015.

Source: Brookings Institution

Both former secretary of education John King and American Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten have done public mea culpas, acknowledging their role in supporting tough disciplinary policies, which they now see differently.

“The students who are most likely to be suspended and expelled are students who we already fail too often,” King, who co-founded a Boston charter school with a strict conduct code, said in a speech last year.

Now a few years in, it remains hotly debated whether moving away from suspensions and adopting alternative approaches like restorative justice has been positive for students and schools.

Using anecdotal evidence and surveys, critics claim that restricting suspensions may have a deleterious effect on school safety and climate, particularly without support, resources, or broader structural reforms. That’s the argument put forth in a report focusing on New York City by Max Eden, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, a conservative think tank that held an April 27 panel on the topic.

“Sadly, the evidence we … have suggests that a policy intended to help minority students has hurt them the most,” Eden wrote in the Daily News.

Yet there are no firm data showing that this is true.

Independent researchers say — and Eden acknowledges — that his analysis cannot show that a reduction in exclusionary discipline caused more negative school climates, including student fighting, mutual respect, and classroom order. In fact, Eden finds that in schools where suspension held steady, there were also declines in school climate — potentially contradicting his argument.

At the same time, the issue of cause and effect plagues many studies cited by advocates for reforming school discipline. While it’s clear that exclusionary discipline is tightly correlated with lower test scores and higher dropout rates — and that it disproportionately affects black and special education students — there are little convincing data showing that suspensions in and of themselves cause these negative outcomes.

Similarly, restorative justice approaches — which emphasize reconciliation of conflict over punishment and are backed by many as a fairer, more effective alternative — have a thin research base.

Careful studies are currently in the works regarding the impacts of the school disciplinary changes sweeping the country. Early evidence and anecdotal accounts suggest that such reforms face a number of hurdles in implementation — especially regarding time, training, and teacher resources — but have the potential to benefit students.

The question likely comes down to the quality of the program put in place once suspensions dwindle.

“When evaluating suspension policies and practices, any impact estimate is inherently a comparison between the existing practice and its potential replacement,” said Rebecca Hinze-Pifer, a doctoral student at the University of Chicago who has studied school discipline in that city. “It is possible we could have dramatically different impact estimates of changing suspension policy depending on the nature of the alternative.”

Weak research that cutting suspensions led to chaos

At the Penn Club in midtown Manhattan, the consensus at the Manhattan Institute’s gathering was that efforts nationally, and particularly in New York City, to reduce school suspensions had backfired. Racial equity, a phrase panelist and conservative columnist Katherine Kersten made a point of putting in air quotes, may be a well-intentioned philosophy, they said, but it simply didn’t work.

Kersten penned an essay earlier this year critical of discipline reform policies in St. Paul, Minn., called “No Thug Left Behind.” It appeared in the City Journal, a Manhattan Institute publication. The moderator delicately referred to the title as “provocative,” but Kesi Foster, of the Urban Youth Collaborative, a group that backs reducing school suspensions, told The 74 that it signals that the author “doesn’t care about the humanity of black people and black youth.”

“The use of the word ‘thug’ in 2017 is not a racist dog whistle, it’s a blow horn,” said Foster.

Kersten did not respond to a request for comment.

The main attraction was Eden’s presentation of his report. He steered clear of such inflammatory rhetoric and acknowledged that there may be good reasons to reduce suspension in schools, but he argued that the research was less definitive than advocates claimed.

“If new evidence from New York City is any indication, discipline reform is hurting the people it’s trying to help and hitting students of color the hardest,” wrote Eden in a March op-ed for USA Today.

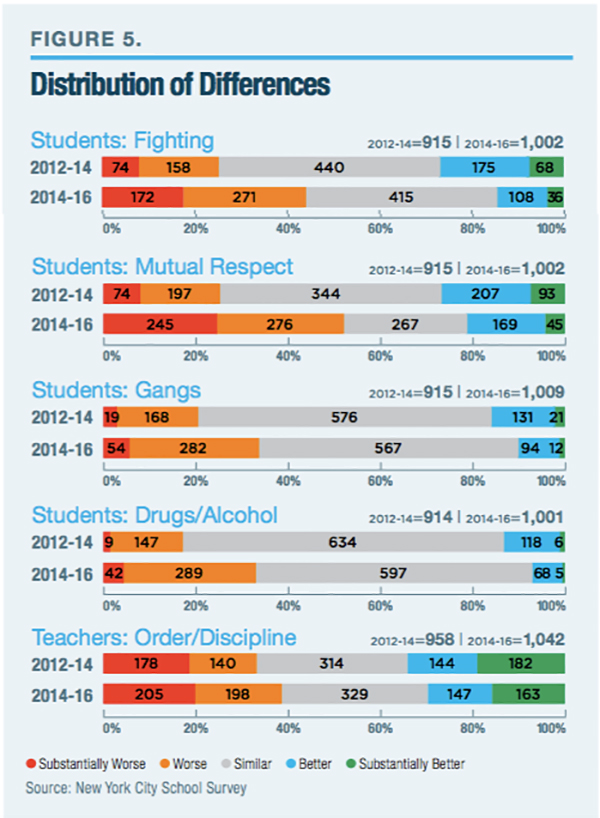

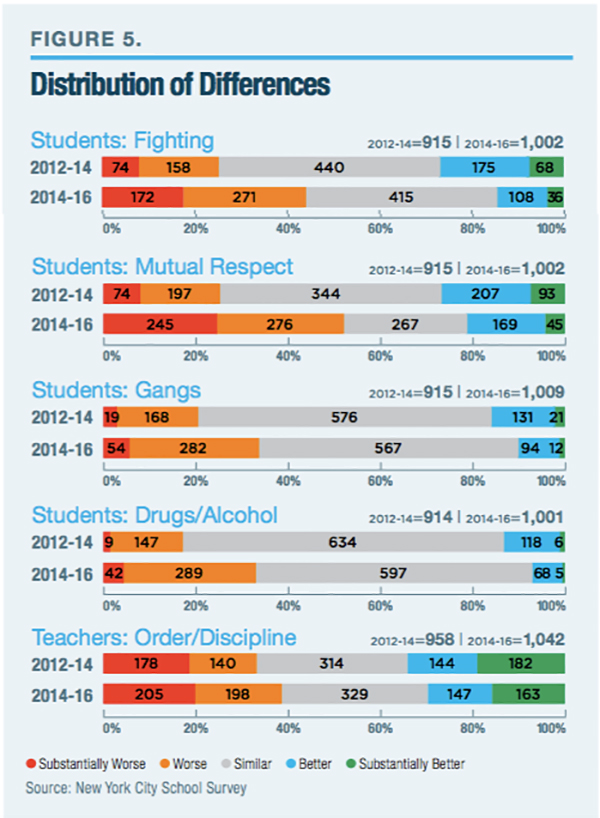

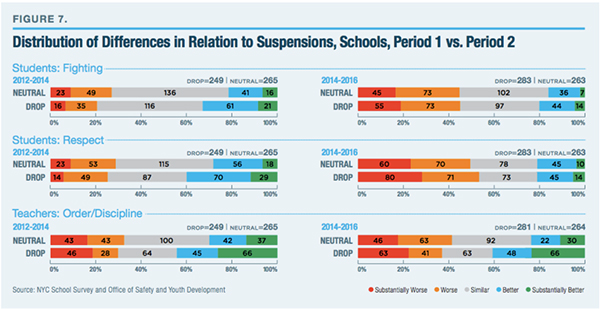

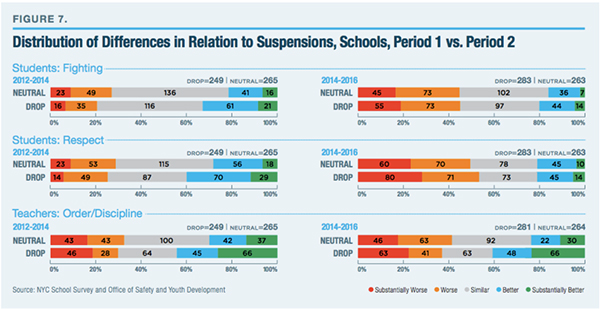

Eden bases his findings on an analysis of surveys administered to teachers and students in New York City. Across a number of indicators, students in hundreds of the city’s public middle and high schools reported less safety and order between 2014 and 2016.

The results were less stark for teachers: A survey question put to teachers asked whether order and discipline were maintained. About 40 percent of schools saw the number of teachers who disagreed or strongly disagreed with that statement increase, about 30 percent saw a decrease, and the remaining 30 percent saw roughly no change.

Source: Manhattan Institute

Eden connects these data to simultaneous efforts by the city to aggressively reduce suspensions and promote restorative justice–style practices.

In spite of the implication in the USA Today piece, Eden acknowledges in the report that he can’t directly link the two. “It is a descriptive, not a causal, analysis of school climate and suspension rates, and the results should be interpreted accordingly,” he writes.

Outside researchers agree that this is a limited approach because it can’t isolate the impact of suspensions.

“It’s taking … mean differences [in climate surveys] and attributing those to reductions in suspensions,” said Matthew Steinberg, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania. “We don’t want to rely … on correlational evidence as if it is providing us with a clear, unbiased, or direct effect of suspensions.”

Another problem for Eden’s hypothesis is that between 2014 and 2016, schools that saw their suspensions drop did not see a greater deterioration in their climate than schools where suspensions stayed the same.

Source: Manhattan Institute

Eden attempts to address this point in the report, saying the key is a change in policy across schools, not simply the number of students suspended.

“The lack of a significant differential between schools that saw neutral and lower suspension rates suggests that the number of suspensions may matter less for school climate than the dynamics fostered by a new set of disciplinary rules.”

Eden’s report does not mention that while the reforms have been in place, New York City schools also saw increases in test scores and graduation rates — though neither can those be connected directly to changes in discipline policy.

Steinberg says that in general there is little evidence on how school discipline reforms impact students.

“Some advocates would want to say if we just eliminate suspensions, things will get better. Whereas others might say, if we eliminate suspensions, things are going to get worse in the schools,” he said. “I would say it’s unclear — because if we don’t address the underlying behavior, then the suspensions are simply picking up behavioral patterns and removing or even keeping suspensions does nothing to change the underlying behavior of students.”

A 2015 study Steinberg co-authored found that when Chicago shortened the length of student suspensions, the effects were mixed: attendance improved, test scores stayed the same, but school climate got worse, according to surveys of students and teachers.

Preliminary results from research that Steinberg is currently conducting in Philadelphia with Mathematica’s Johanna Lacoe provides some reason for modest optimism regarding recent reforms. After the city moved away from zero-tolerance practices and reduced suspensions, Steinberg finds that serious behavioral misconduct decreased and student achievement was unaffected, relative to other Pennsylvania school districts.

Without suspension, would students do better or worse?

But if Eden’s research is limited, so are studies frequently promoted by advocates of reducing suspensions.

“The logic behind the discipline reform push was predicated on two assumptions: one, that suspensions harm students, and two, that the racial disparities are largely attributable to teacher bias,” said Eden. “Both of those assumptions are intuitively plausible [but] not supported in any convincing way by the existing research.”

To study the impact of suspensions, research often compares students who are suspended against peers who are not suspended while also being similar across a variety of observable dimensions, such as gender, race, poverty level, and prior test scores. Any difference in academic performance, some argue, can then be roughly attributed to being suspended.

As one oft-cited report put it, “When controlling for campus and individual student characteristics, the data revealed that a student who was suspended or expelled for a discretionary violation was nearly three times as likely to be in contact with the juvenile justice system the following year.”

Another analysis, by UCLA’s Civil Rights Project, estimates the effect of suspensions on dropping out of high school, and uses this finding to argue that exclusionary discipline costs the nation billions of dollars annually in lost student earnings and increased government spending. The researchers compared students who are suspended against those who aren’t but otherwise look similar on paper.

Steinberg said that existing research is limited in its ability to truly gauge the impact of suspensions on either those students who are removed from school or those who aren’t.

“By and large, the evidence is correlational. There’s been years of research that shows that students who are excluded through out-of-school suspensions have lower test scores, are more likely to drop out, have a host of adverse academic outcomes,” he said. “The difficult empirical question is, in the absence of the suspension, would [those same] students have done better or worse?”

Hinze-Pifer agrees. “There is so much selection in student discipline data, in how students get entered into the data, and in how consequences are meted out, that controlling for observable [characteristics] does not lead to a compelling causal estimate.”

Russell Rumberger, a professor of education at the University of California Santa Barbara and author of the UCLA report, acknowledged the limitations of his approach but argues that it is still useful.

“There’s not a definitive way of doing this,” he said. “What we do and what’s done in the research literature is to identify other factors that may explain the suspensions and control for those factors.”

While Hinze-Pifer says there are problems with this approach, she also points out that there are strong theoretical reasons to suspect that suspensions have negative impacts on students.

“Hours in the classroom do affect student learning,” she said. “By its nature, suspension separates a student from that instructional time.”

One recent study found that suspensions do not harm — and may very slightly help — students’ test scores in the year after they are suspended, but another showed that suspensions increase the likelihood that students will be held back the following year. Steinberg says his preliminary work finds that suspensions do, in fact, cause drops in test score in the year of the suspension.

Meanwhile, there is little if any research showing that suspensions are an effective way to deter or improve student misbehavior. Similarly, research is limited on how suspensions impact the school as a whole, including the academic achievement of non-suspended students. Existing studies are mixed.

“Suspensions and police do not make schools safe,” argues Donavon Taveras, a Brooklyn high school student who works with the Urban Youth Collaborative. “Strong communities make schools safe.” Research shows that schools with positive relationships among staff, students, and parents are safer and have lower suspension rates.

On the question of racial disproportionality, research suggests that teacher and administrator bias may partially explain the differing rates of discipline by student group — though it’s not clear if this explains all or most of the gap. One study showed that black teachers are significantly less likely to suspend black students, particularly for offenses that involve teacher discretion.

But some research indicates that within the same school, black students are only slightly more likely to be punished for the same offense as white students. Another recent study of preschool teachers found that although they were more likely to track the behavior of black children, they were no more likely to recommend suspensions relative to white students.

The shift to restorative justice

Even supporters of reducing suspensions agree that doing so is only a partial solution — what replaces exclusionary discipline is also crucial.

Here there is some research to go on. Supportive evidence exists for programs including Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports, a school-wide initiative that encourages and rewards good behavior, and Caring School Community, which emphasizes improving school climate and solving problems collaboratively between students and teachers. One method of teacher training stressing empathy with students made those teachers much less likely to issue suspensions in a small trial study.

Perhaps the most commonly backed initiative among critics of exclusionary discipline is restorative justice, also referred to as restorative practices. Supporters describe this as a systemic approach that emphasizes a community process — rather than punitive discipline — in response to misbehavior. Although case studies and anecdotes suggest restorative justice can be effective, little if any rigorous research has been conducted showing as much.

“Restorative justice is not a practice; it’s a shift in environment,” said Christine Rodriguez, a recent New York City high school graduate who works with the Urban Youth Collaborative. Advocates for the approach generally agree that it takes significant time, resources, training, and buy-in to implement effectively.

Efforts to reduce suspensions are also likely linked to broader education policy issues: school funding, insofar as replacement programs require resources to implement well; school integration, since exclusionary discipline is heavily concentrated in segregated schools; and teacher diversity, because it’s been linked to reduced suspensions among black students.

Eden argues that because, in his view, there is so little evidence to support prevailing reforms and suggestive evidence that it’s backfired, districts should roll back, halt, or re-examine efforts to limit suspensions.

“In some ways, the paper is an effort to inject an aggressive dose of humility into the debate,” said Eden. “It cast[s] very grave and serious doubts to the claim that [discipline reform] is working and that there’s no cause for concern.”

Everyone seems to agree that more research is needed but that policymakers can’t wait for the perfect study — they just disagree on what should be done at present.

“No one who is a serious discipline reform proponent is saying schools should do nothing,” said Dan Losen of the UCLA Civil Rights Project. “What we’re saying is that there are appropriate interventions that help students succeed and stay in school and that we’re all better off as a society if we pursue those instead of just kicking kids to the curb.”

But, he said, “We all want better research.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)