The Mentor: One Year, Two Teachers and a Quest in the Bronx to Empower Educators and Students to Think for Themselves

By Kate Stringer | June 24, 2019

New York City

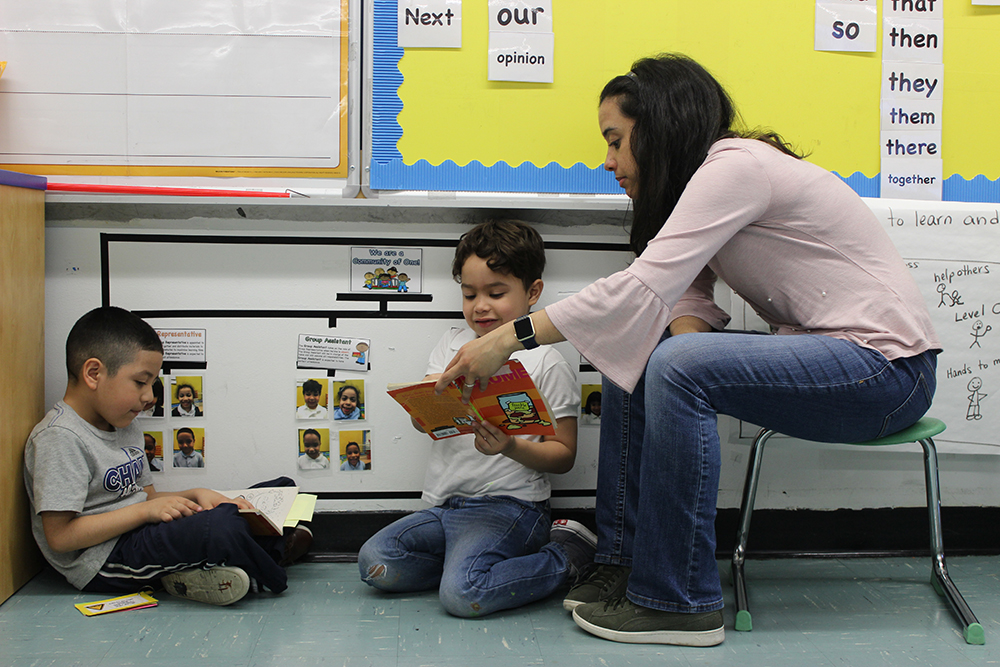

Kindergarten teacher Elisa Espinal asks her students a lot of questions.

She knows this because her mentor, fifth-grade teacher Ambar Quinones, wrote down everything Espinal said by the minute — at 11:08 a.m., 11:09 a.m., 11:10 a.m. — during one class period on a freezing, sunny day in mid-December.

“Why do you think you ask so many questions?” Quinones asks her.

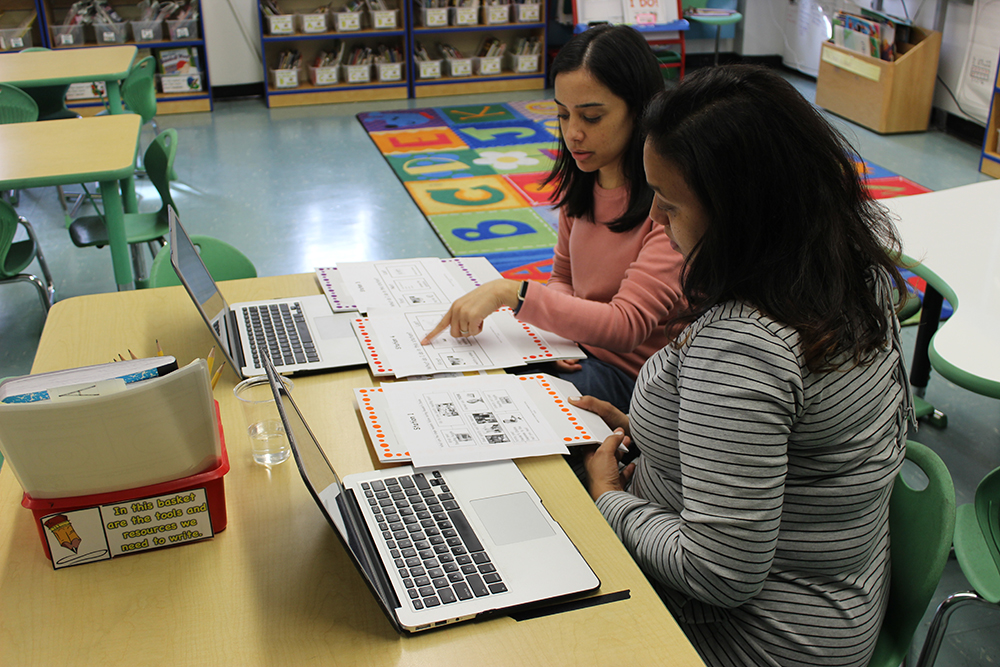

Espinal laughs as she leans over the precise notes Quinones typed on her laptop. The two are sitting alone in Espinal’s classroom at Concourse Village Elementary, a school in the South Bronx. It’s a brief moment of quiet when her kindergartners are with another teacher. Like all teachers, they have expertly fit themselves into places sized for kids, perched on small green chairs that comfortably fit a 5-year-old.

“I’m sure it’s because I’m trying to get an answer,” Espinal says. “You’re trying to guide their thinking,” Quinones nods.

This particular lesson was about a book character named Pete the Cat, who had acquired some new white sneakers and immediately got them dirty. But Pete was a positive soul and didn’t seem to mind.

Espinal asked her students what they learned from Pete the Cat. One kindergartner responded that she learned Pete stepped in strawberries. “Not really what I was going for,” Espinal tells Quinones.

Quinones was also a kindergarten teacher a few years ago, her first job at Concourse Village Elementary. She remembers how challenging it was to get 5-year-olds to stand still in line, much less wrap their heads around big questions of meaning and motivation.

“What I used to do when I was in kindergarten is ask, ‘What did Pete the Cat learn at the end of the story?’” Quinones says. “So you’re putting [the question] on the character, not them.”

These moments are both striking and frequent in these sessions, when the parallels between mentoring a teacher and teaching a student become evident. Quinones wants to guide Espinal’s thinking just as much as she wants Espinal to guide her students’ thinking. Part of the challenge for both a mentor teacher and for a classroom teacher is to not tell their pupils what to think, but to teach them how to think for themselves.

“That’s the most powerful idea — that you can do things on your own to move you to the next level,” Quinones says.

Espinal and Quinones meet weekly for mentoring sessions, forming the kind of close relationship over the course of a year that many teachers in a new school yearn for. While the two have similar backgrounds — their families are both from the Dominican Republic and they grew up taking frequent trips between New York City and the DR — they are very different people.

Espinal, 34, is quiet and introverted, but she amplifies her energy when she’s with her young students. She has an innate skill for getting kindergartners excited about learning, making faces of surprise and excitement about the mysteries of phonics that are often reflected in her students’ faces. She wears jeans so she can sit crisscross on the floor and match her 5-year-olds’ height. While Espinal is drawn to the kindergartners, she still misses the 3-year-olds she taught for seven years before coming here.

Quinones, 36, is extroverted and quick to laugh but has a wise, professional demeanor in her work with other teachers and her own fifth-grade students. She’s often looked to for guidance, not just from Espinal but many other educators at Concourse Village as well. Quinones is incredibly hardworking, a trait she learned from her mother, a lawyer, and is able to balance a thousand tasks at school and at home, where she’s the mother of a 10-year-old. Her natural leadership skills will propel Quinones toward a major career change this year.

The two women are part of the New Teacher Center’s mentoring program, one of the largest and most recognized mentoring programs in the country. Nearly 8 in 10 new teachers in the U.S. receive some form of mentoring, but few receive mentoring as robust as the New Teacher Center’s model, with professional development, coaching, two years of mentoring and an online platform to share feedback. When it comes to improving things like student achievement, teacher practice and retention, the quality matters.

The New Teacher Center has been around for more than 20 years, growing from a small program created by Ellen Moir out of the University of California, Santa Cruz, to a national nonprofit that’s impacted 250,000 teachers, with annual revenue of more than $35 million. The organization also received two multimillion-dollar federal grants to expand their work. Moir retired last year, handing over the organization to Desmond Blackburn, who adjusted the mission statement to include an explicit focus on student equity.

“Our mission is to disrupt the predictability of educational inequities for systemically underserved students, from preschool through high school, by accelerating educator effectiveness,” the new statement reads.

Research on the program has pointed to gains in student achievement and teacher retention in certain districts. But there have been growing pains, and as the program has expanded to areas of greater need, where schools have the fewest resources and teachers the least experience, large-scale, rigorous studies of the program have not shown improved effects on teacher retention (they didn’t show negative effects either). However, recent analyses by the New Teacher Center for Bronx District 7 — where Espinal and Quinones teach — and districts 9, 11 and 12 found that 80 percent of the new teachers who participated in its mentoring program were retained after one year, compared with 72 percent of a matched comparison of their peers.

Mentoring can’t fix everything, and it’s only one part of a comprehensive induction program to support new teachers, researchers argue. But as teacher walkouts across the country this past year show, teachers are feeling drained and demanding support.

And novice teachers in high-need districts such as Espinal’s in the South Bronx need the most help. New York City specifically has made a big bet on teacher mentoring, partnering with the New Teacher Center to bring its program to 123 schools this past year, the majority of them in the Bronx. The program works with 217 mentors and 487 early-career teachers. The Department of Education paid NTC $1.7 million during the 2018-19 school year; some of the other work is covered by federal grants.

Many say teaching is a lonely profession, especially during the first few years. “Teachers are very isolated throughout the day,” said Marla Shelton, a mentor and educator in District 12. “We stay in our classroom and don’t make friends right away.”

Teachers, who are now mentors, remember early in their careers watching their more experienced peers eating lunch together and wishing they had those connections. Some admonish their past selves for not becoming friends immediately with the secretaries and janitors and security guards. They wish they’d had someone to turn to and say, “Is it OK that I’m feeling this way?”

“A mentor gives you someone you know you can go to and ask the questions you don’t want to ask other people,” said Allison Bondell, also a teacher mentor in New York City. “It forces you to build relationships with people who know the school.”

The 74 spent one academic year documenting Espinal’s and Quinones’s journey to see how important these relationships are to the success of a new teacher, whether their bond could convince an uncertain Espinal to return to Concourse Village, whether Quinones could accomplish all that she wants to in what may be the last of her intensive mentoring partnerships before she gets an unexpected promotion and — perhaps most critically — if their time together makes a difference in the learning of Espinal’s kindergartners, an eager, adorable bunch who call one of the country’s poorest zip codes home.

September

Concourse Village Elementary School is located inside an old brick building, but the staff have found a way to make it welcoming. To get inside the front entrance, families pass a giant colorful collage of students and make their way up a bright blue staircase that leads to similarly vibrant doors. The school sits on Concourse Village West, a few blocks south and east of Yankee Stadium, and shares not only a basement with a charter school but its entire block with three other schools.

In a way, it’s surprising that Elisa Espinal decided to come here. Espinal is a homebody. She lives in the same apartment building where she grew up in Brooklyn. After she graduated from City College in Manhattan with a degree in psychology, she worked at the same child development center she attended when she was 2 and she taught at a public school in her neighborhood. But this year, at 6 a.m. every morning, she hops the M line and then the D, commuting an hour by subway to reach Concourse Village. She’s doing it for a reason.

Espinal wants to be a better teacher, but she hasn’t been satisfied with the experience she’s had. She spent seven years at a child development center in Brooklyn while earning her teaching certificate and master’s, and then three more at the public school shuffling through different grades. Her theory is, she could work in any school for a long time and gain experience but maybe develop bad habits. Or she could move somewhere good and learn fast.

Concourse Village Elementary is somewhere good. The pre-K through fifth-grade school is doing incredible things: 87 percent of its students are proficient in reading, while 88 percent are proficient in math. That’s nearly double the 45 percent of students statewide who are proficient in both subjects and far outpaces academic performance in its South Bronx neighborhood, where just 58 percent of students graduate from high school in four years and only about 1 in 4 students can read and do math at grade level.

More than 90 percent of Concourse students are low income, 18 percent are homeless and 23 percent are classified as special education. Nearly two-thirds of students are Hispanic, one-third are black and — in a school where 11 different languages are represented, from Yemen to different parts of Africa, the Dominican Republic, Mexico, Ecuador, Panama and Puerto Rico — 19 percent are English learners. The school’s stellar outcomes have received press attention and the Blue Ribbon School of Excellence award from the U.S. Department of Education, one of just eight New York City schools to get the honor last October. Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza made Concourse Village one of the first schools he visited during his early weeks on the job.

Principal Alexa Sorden founded the school in 2013 to replace the long-failing P.S. 385 that used to operate in that building. Sorden hired her own staff and was determined to make this her dream school, with high standards for students and a positive disciplinary environment where students felt safe to learn. Sorden, who sends her own children here, said she gets her indefatigable optimism from her mother.

Espinal came to Concourse after being let go from her old school when enrollment shrank. She had seen videos touting the school’s success and applied. The kindergarten team and Quinones interviewed her — Sorden wasn’t even involved. Her theory: she wanted her team to start taking ownership of their other team members. Quinones recalled being struck by the level of preparedness Espinal brought to the two demo lessons she did during the interview process.

When Espinal started, she was immediately shocked by the strong culture of the school. It was almost overwhelming. Staff here say that, regardless of your teaching experience, being a new teacher at Concourse feels like being a first-year teacher. Espinal was told that her kindergartners were going to be able to read Judy Blume’s Freckle Juice by the end of the year, a 64-page book targeted at third-, fourth- and fifth-graders.

“I was like, ‘You’re joking, right?’” Espinal says. “Because at the beginning of the year, the kids didn’t know their letters. How are we supposed to get them there?”

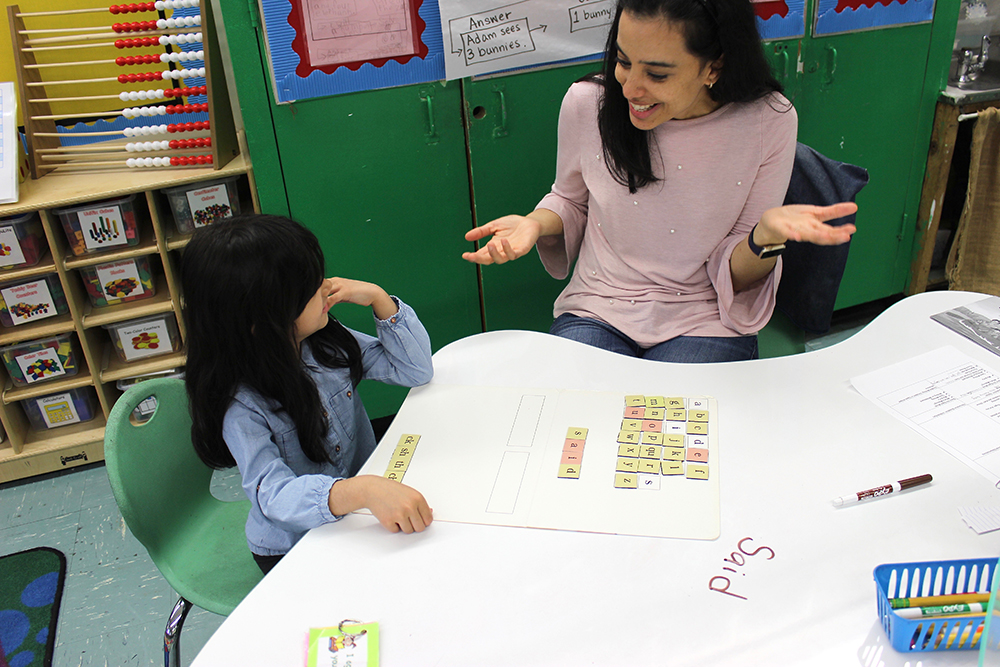

At one of Quinones’s and Espinal’s first meetings, though, it wasn’t curriculum that had Espinal concerned but classroom management. Her kindergartners would shout things out as she tried to teach a lesson. She wanted to tell them to be quiet, but she also wanted to ignore them so that she wasn’t also interrupting her own lesson. Yet, left unaddressed, the students just kept talking.

Concourse Village uses a behavioral system called PBIS, which stands for Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports. Teachers encourage students for their good behavior and try to be conscious of not inadvertently rewarding problem behavior. That way, when students are publicly acknowledged for actions like staying on task or listening to a teacher, other students who also want attention will start behaving similarly. PBIS also recommends that educators use a common system and language across the school: At Concourse, there are charts on the walls to show the level of volume students should be at. A level zero would be absolute silence, but higher levels would allow for quiet chattering.

“I’m using the level zero a lot, but it doesn’t work,” Espinal tells Quinones in one of their first mentoring meetings.

“Just try to be more consistent,” Quinones says. But then Quinones adjusts her speech. The New Teacher Center coaches its teachers to use specific language when listening to their mentees. So instead of saying, “You should do this,” teachers can say, “Perhaps X might work,” or “When I consider X, I always think about…” A mentor isn’t always going to be around to give solutions, so these questions can reframe how the new teachers think about solving problems.

“What I have done in my room,” Quinones begins, “is we have a star and we put the star where the expectation for the voice level should be. So having that star at level zero, you don’t have to put your hand up, you can just point.” Quinones says she no longer has to interrupt her lessons to tell students where their volume should be, simply pointing at the volume expectation as she continues teaching. But Quinones also learned that she couldn’t always expect students’ voices to be a level zero. She had to give her students freedom to talk, to show them that there is a time and place for certain volumes.

This is Quinones’s second year as a mentor through the New Teacher Center. NTC operates on the premise that a new teacher should have at least two years of intensive mentoring, but sometimes the organization works with schools for three or even four years.

On a September morning last year, Quinones is sitting at tables with nearly two dozen other mentors at a community center in the Bronx. These mentors, all in their second year of training with the New Teacher Center, were discussing topics like race and equity and how that influences expectations of students. One mentor shares that her mentee was looking at students with a deficit mindset, something she’s trying to change.

“When teachers say, ‘My student can’t do this,’ my response is, ‘Well, what can they do?’” the mentor says.

A two-day professional learning session is a lot of time to be absent from the classroom, and some teachers miss these sessions because they can’t get away. But part of the philosophy behind the New Teacher Center is that mentor teachers cannot be a mentor simply because they have lots of experience in the classroom — they need training to do it right.

“There’s a misconception, ‘Oh you’re a good teacher, you can mentor others,’” Quinones says. “This is a skill, to mentor someone.”

Over the past two decades, the New Teacher Center has grappled with how to select and train mentor teachers. While they have selection criteria for schools to use — picking teachers who demonstrate leadership, have highly effective instructional practice and are collaborative — it doesn’t always work out. Sometimes a school is packed with new teachers and there are few options. Other times, teachers who might not currently demonstrate leadership skills are looking to develop them, so principals might allow them to be mentors rather than selecting other educators already in leadership positions.

But they’ve also learned that mentors have to meet some criteria to be successful. This lesson was apparent in their first venture into New York City, back in the early 2000s.

In 2004, New York state passed a law requiring that all first-year teachers receive mentoring. The New York City Department of Education decided it was going to invest in a citywide mentoring model costing about $40 million a year, and it partnered with the New Teacher Center to hire 500 mentors. The city was mostly able to follow the New Teacher Center’s model, except that it could only afford to have the teachers be mentored for one year, not two as NTC prefers, and the mentor teachers had a higher ratio of mentees than NTC prefered — at the time, the city assigned 17 mentees per mentor, while the Center recommended 12 to 15 per mentor, according to EdWeek. The mentors floated between schools and didn’t understand the culture of individual school buildings.

A 2008 study from Columbia University of the program found little evidence that it improved teacher retention, reduced teacher absences or improved student achievement. However, it did find that when mentor teachers had more knowledge of the school they were in, retention improved in that school. It also found that student achievement was higher when a teacher had more hours of mentoring.

“On the issue of retention, there is particularly strong evidence that having a mentor who previously worked in the same school as a mentor or teacher has an important impact on whether a teacher decides to remain in the school the following year,” researcher Jonah Rockoff wrote. “This suggests that an important part of mentoring may be the provision of school specific knowledge.”

Bondell, the NTC mentor in the Bronx who has been teaching for 13 years, experienced this firsthand. In her first year, she was assigned a mentor who didn’t work in her school. Their visits were once a month, but Bondell didn’t feel that her mentor understood what she was going through. The mentor would say things like, “The students aren’t behaving,” but would have no helpful way of connecting it to the context of the school, she said.

“I felt like she had no idea of my struggle. She could listen to me, but she didn’t know anything [about my school],” Bondell said. “But with [NTC], you’re in the same boat with people, so you really do want to help, you want to see a change, you want to make a difference because you know what they’re going through.”

October

It’s a cool, overcast day at the end of October, and the kindergartners at Concourse are rushing to put their things away before they leave for their next class. Mission: Impossible’s iconic theme song plays, urging them on in its high-adrenaline bop. Across the school, students hear this every time they transition between subjects.

Now, with a quiet classroom and her mentor, Espinal begins asking herself a lot of questions.

“I’m learning to always question why I’m doing things.” —mentee Elisa Espinal, kindergarten teacher

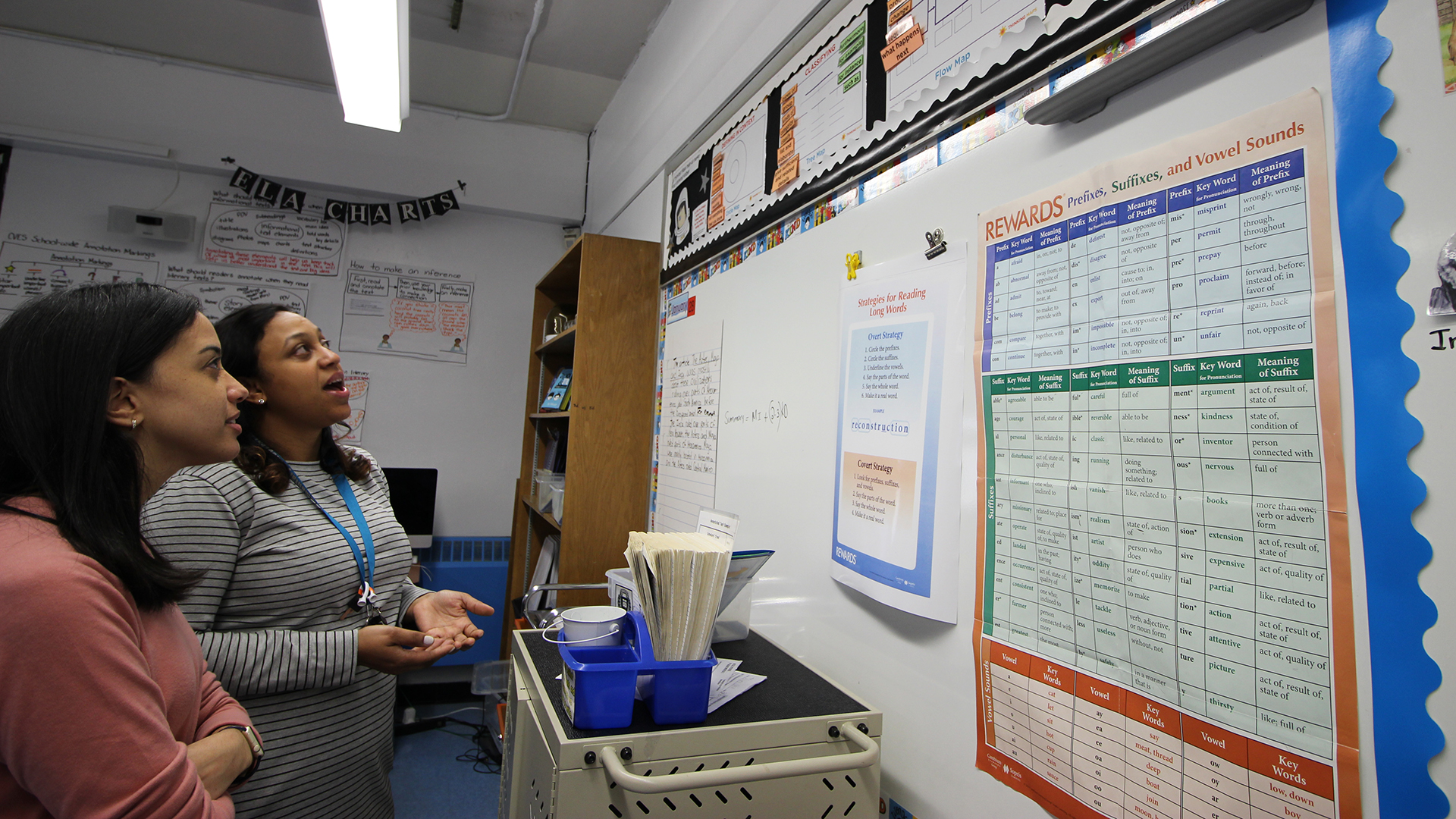

Every lesson, every poster in her classroom, it all has to have a purpose. During this mentoring session, Quinones stands up to look at one of the charts in Espinal’s classroom. The chart asks, “Why do we read?” and includes answers like “to laugh,” “to learn” and “to make a choice.”

“I want the students to read for fun,” Espinal explains. So often, her students are just reading to say they’re done. But she wants them to enjoy it.

“We want to create adults that love to read,” Quinones says, nodding. “I see you have a chart. I wonder if it will actually help them?” Quinones recommends that Espinal look at a similar chart that another teacher has hanging in her classroom that also includes a few more reasons why students read, with graphics to visualize the concepts for the young students. Modeling her chart off of that one will also create more consistency across the school, Quinones points out.

“I’m learning to always question why I’m doing things,” Espinal says later. “If I’m doing something with kids, I want it to be fun and engaging. But as much as it’s fun and engaging, how does it really help students progress in their level?”

Concourse Village has a very strong culture, intentionally set up by Sorden, the principal. She was bothered by past schools she’d been in, where each teacher ran their classroom separately from the rest of the school, as if it were their own business. Instead, she wants her school to be like Starbucks: When you walk into a Starbucks anywhere in the U.S., you expect the coffee to be the same. At Concourse, every classroom plays soft jazz music while students work. Every student learns how to agree and disagree with their classmates using the same notecards with sentence starters on them, such as “I (agree/disagree) with you because… .” Every teacher stands outside their door and greets students. Perhaps most radically and definitely nothing like Starbucks: Teachers can’t drink coffee or use their cell phones in front of students.

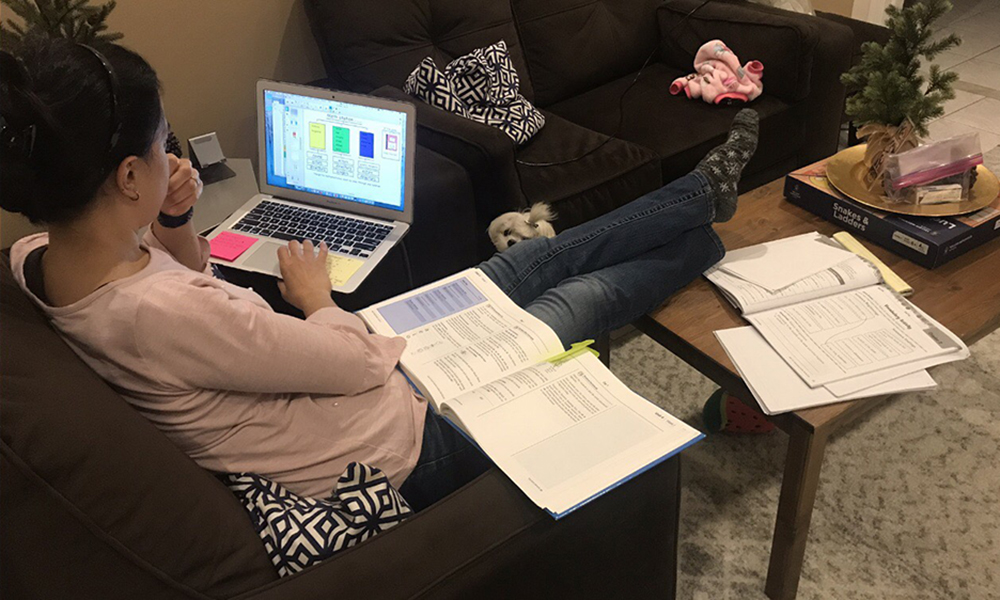

But diving into this culture and keeping pace with it takes time. Espinal works seven days a week to stay on top of everything. When she comes home from work, she stops by her mom’s house for dinner before heading the few blocks to her own apartment, where she sits on her couch with her Maltese dog, Macy, working, grading student work and responding to emails, often until bedtime. Her husband, a software tester, also works in their apartment office.

“When I’m having a tough time, I think about the parents of the kids who are depending on me to learn whatever they need to learn.” —Espinal

Quinones has a few recommendations that she’s found were helpful in the past: giving students responsibilities in the classroom, such as helping to prepare the technology, by laying out the iPads and setting up the headphones. Quinones also shared how Espinal could find audio readings of books for students to follow along with, because it would add a level of mystery for the students to hear their book read by another person and give Espinal’s voice a break during the day.

As she’s talking, a poster in her classroom falls off the wall. “Ahh, I can’t use that tape,” Espinal says, lamenting choosing the Scotch tape inherited from another teacher. “I need to use packing tape and nothing else!”

Espinal knew she wanted to work with children from a young age, when she would help her mom look after other people’s kids during the day. Her parents are from the Dominican Republic, so she and her family would often take trips there to visit. Espinal would pack all of her art supplies so she and her younger cousins and the kids in the neighborhood could make art projects together. One time they made a papier-mâché project that took three days. She and the children sat under a tree ripping up newspaper, gluing the pieces together and then watching it dry in her grandma’s house.

“When I’m having a tough time, I think about the parents of the kids who are depending on me to learn whatever they need to learn,” Espinal says. “I think about my nieces and nephews, and how I would want them to get a good education.”

When good teachers leave

Before Ellen Moir founded the New Teacher Center, she used to lead the education department at the University of California, Santa Cruz. But she would get calls from some of her best student teachers who were considering leaving the profession in October of their first year.

“It haunted me,” Moir said. “It pushed me hard to figure out what was going on.”

She discovered that when she was able to build intimate communities of experienced teachers who could support the new ones throughout their first year, those new educators would be more successful. Moir started to create a model out of this idea and shared it with others across the state. By 1998, two funders had approached her with the offer of expanding the program nationally.

Since then, the program has grown from one with a few funders to one with upwards of $35 million in yearly revenue. During Moir’s 20 years, 250,000 new teachers, mentors and coaches were impacted by the New Teacher Center, according to its estimates.

By the end of the 2018 school year, NTC was working in 27 states and in 400 school districts. It estimates that 24,000 new teachers were being supported by 6,500 mentors and coaches, reaching a total of 1.8 million students that year.

“I think every teacher in America needs that kind of side-by-side instructional and emotional support,” said Moir, now retired and living in Santa Cruz. “We created a movement across America. I’m proud of that.”

But every movement, particularly one that explodes nationally as NTC did, faces significant hurdles.

In some of the individual school districts where NTC has worked, the organization has been able to show improved retention rates for new teachers. But as the organization started to expand across the country to school districts with more low-income, urban populations, it started to struggle to produce the same results. A 2010 randomized controlled trial of NTC from Mathematica Policy Institute found that while two years of mentoring could boost student achievement, there were no positive effects on retention.

“It haunted me … It pushed me hard to figure out what was going on.” —Ellen Moir, founder of the New Teacher Center

Moir said NTC never should have participated in the Mathematica study because, at that time, the organization had not worked in enough large urban districts. But later in the conversation, she reflected, “It’s good we did work with Mathematica, because we learned a lot.” After that, NTC would begin focusing on large districts, often in urban, low-income school systems. Because it had seen positive results for students in high-need areas, the organization started applying for grants to help quantify and expand that work.

Much of the subsequent money came from two federal grants from the Obama administration. These were called Investing in Innovation (i3) grants, funds given to further the administration’s reform efforts; in the case of NTC, supporting effective teachers and principals. The first was a “Validation” grant, which they received in 2012, meant to validate and spread programs with moderate evidence. A few years later, NTC earned a “Scale-Up” grant, meant to expand programs with strong evidence.

The validation grant kicked off NTC’s work with Chicago Public Schools, Broward County Public Schools in Florida and Grant Wood Area Education Agency in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. A study from SRI International on outcomes there again found increases of several months in student achievement but no significant results in teacher practice or retention.

Richard Ingersoll, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education, analyzed the Mathematica study and the seeming inconsistency of having improved student achievement but flat teacher retention rates. He said this finding may speak to the challenge of mentoring programs in large, low-income schools. Even though a teacher may have a great mentor who can help them deliver better results for students, that relationship might not be enough to keep the teacher in that school or that city.

Mentoring and other forms of teacher induction have grown more common in the United States, with 81 percent of first-year public school teachers saying they received mentoring, according to an analysis by Ingersoll. Many states, such as New York, even have laws that new teachers must receive some form of mentorship or support in their first year.

A longitudinal look at teacher retention found that by year five, 17 percent of teachers had left the profession, according to the U.S. Department of Education. But retention rates were higher for those teachers who had a mentor. It’s worth noting that the rate of educators who quit the profession may be lower than the average quit rate for other professions, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. This past year, the rate was 0.8 percent for workers in state and local education industries (this includes employees who are not teachers), but 2.3 percent for all American workers.

In a 2011 review of studies conducted around teacher mentoring, Ingersoll and Michael Strong found that teacher mentoring had positive effects on factors like student achievement, teacher retention and teacher practice.

But mentoring is not the sole solution to supporting teachers, Ingersoll said. Schools should look at multiple methods of helping teachers, from orientations to giving them opportunities to collaborate to regularly meeting with the principal.

“That’s not cost-free; that’s going to waste money.” — Professor Richard Ingersoll

If you don’t provide teachers with some of those supports, “you’re going to lose potentially a lot of good teachers after a few years,” Ingersoll said. “That’s not cost-free; that’s going to waste money.”

Mentorship is also good for the mentor and a tool to keep veteran teachers around, said Emily Davis, founder of the Teacher Development Network, who also used to work as a senior director for NTC.

“They end up feeling efficacious in their own work,” Davis said. “They have a teacher leadership role and they learn about their own practice.”

November

Maybe it’s because there are only a few days left before Thanksgiving break, but the kindergartners are especially energetic today, bouncing and singing loudly and turning in place on the rainbow-colored rug.

“Wait, hold on,” Espinal says, standing at the front of the room and clapping. “Can we hold this in our minds for later? You can talk about this at recess time.”

Espinal has learned that she has a lot of power over how excited kindergartners can be about something. It’s a double-edged sword. On the one hand, she can get them bobbing about learning obscure words like “pufferbellies.” On the other hand, they can be so excited, they can’t stop singing about the pufferbellies down by the station early in the morning.

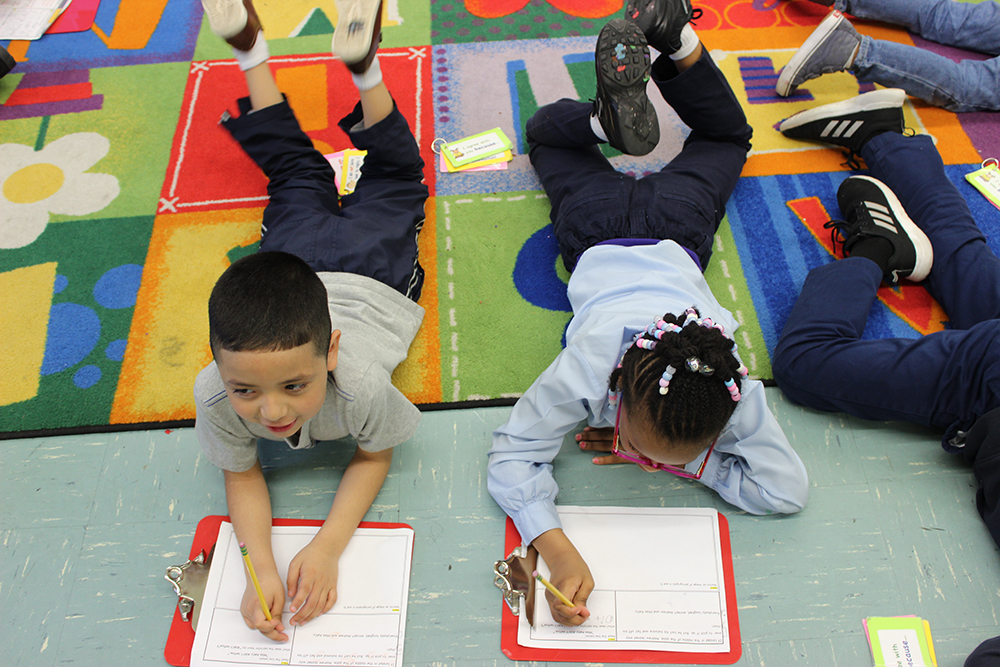

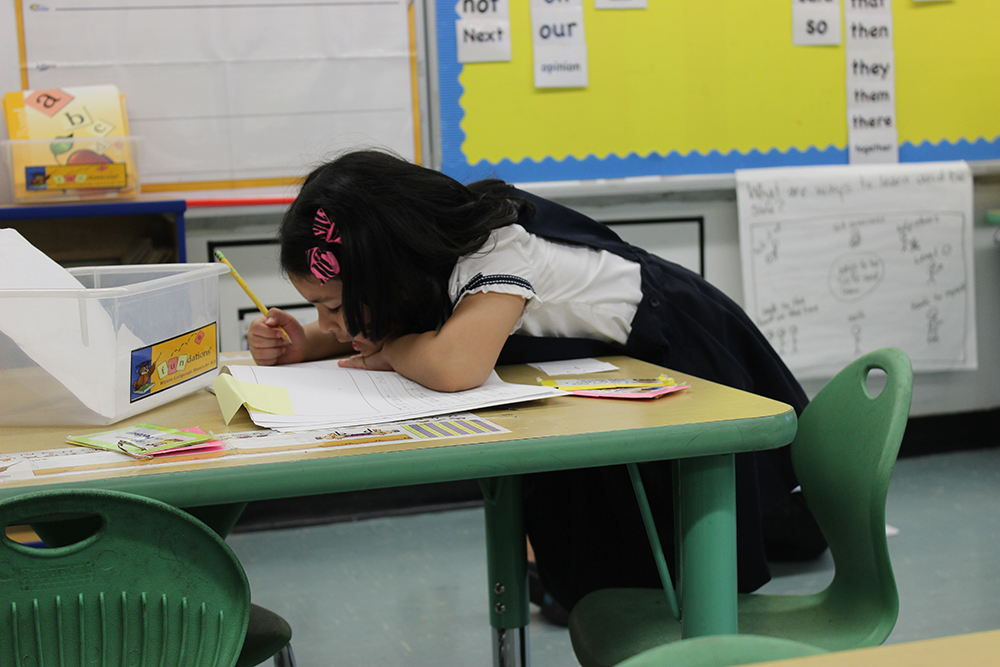

But the kindergartners are progressing. Espinal has started dividing her students into reading groups based on their abilities: those who know most of their letters but need to work on sounds, those who are starting to write sentences, and those who are so advanced that they can take the sounds of words they know, like “at,” and use them to help read other words they don’t know, like “that.”

She’s also trying to help her students work more independently, just like she observed in her colleague’s first-grade math classroom. Soon, Quinones tells her during their mentoring session today, “it’s going to be less Ms. Espinal and more student-centered.” But these are kindergartners, and she’s not sure if they’re ready for that.

“Go back to what you said before,” Quinones points out. “Who is ready and who is not?” Together Espinal and Quinones list off students who might be able to work on their own and could thrive from having more responsibilities.

Today, Espinal and Quinones are sitting in the kindergarten classroom grading student work on this bright, cool November day. Espinal had asked her students to write a sentence using “I like” and ending with what they like to drink. Quinones asks her what she wants to grade the students on. At first, Espinal says she just wants to see if the students can write “I like” and if they can say what they want to drink. Quinones types Espinal’s expectations into the grading tool from the New Teacher Center. As they look at the work, they have to decide if each student is approaching, meeting or exceeding expectations.

But just as there are a thousand things to think about when teaching, Espinal realizes there are also a thousand things she could be grading.

One student’s paper says “I like to juice.”

“She’s approaching,” Espinal says, explaining that she didn’t use the word “drink” and the sentence doesn’t make sense.

But having the sentence make sense wasn’t originally part of her expectations for the students, Quinones tells her.

“Oh, I see — I was looking for two things,” Espinal says.

“So your criteria is the sentence needs to make sense? Or maybe it has to be a complete sentence?” Quinones asks.

Espinal nods. This is one of her biggest challenges, one she will wrestle with throughout the course of the year. “I like the focus because one of my struggles is I want to work on everything.”

January

The emotions of a new teacher can ride a curve, up and down, from delight to devastation. As she began her work with new teachers, Moir tracked these feelings, mapping out phases of a first-year teacher on a graph with intermittent highs and lows, an idea that is now widely cited. In January, fresh from winter break and with four months at this new school under her belt, Espinal is entering what Moir called the “rejuvenation phase,” during which teachers reflect on their practice and accept the real challenges of their profession.

Espinal is incredibly detail oriented, so much so that it’s sometimes unbelievable to watch. During one lesson, she reads aloud a story, arriving at the part where one of the characters in the book passes another a secret recipe. At this exact moment, Espinal pulls a piece of paper out of her pocket that she’d placed there in advance and unfurls it, as though she herself had just found the secret note from the book. The kindergartners visibly bounce with joy.

But being so keyed into details means she’s hyper-aware of all the other ones she hasn’t gotten to. Even though she can stay up late planning the next day’s lesson, she still feels as though she’s missed something.

At a weekly meeting in January, Quinones is advising her to prioritize. “As teachers — it happens to me all the time — we have a big umbrella of responsibility. There’s so much we can tackle, but when we prioritize, it’s more effective.”

“It just feels like you’re neglecting something else,” Espinal says. “It feels like, ‘Oh, man, I forgot to do that.’ Because there are so many little pieces to prepare.”

In December, Principal Sorden said Espinal was doubting whether she could teach kindergarten next year. “She’s like, ‘I really like little kids.’ I’m like, ‘They’re kindergarten,’” Sorden said, pushing back a bit. But Espinal loved the 3-year-olds she used to work with in Brooklyn at the child development center, and she missed how she could connect and be animated with them.

During moments of self-doubt, Quinones encourages her to think about the things she is doing well with her students.

“When you’re thinking, ‘I missed something,’ or ‘There’s so much to do,’ there’s always something that we did do that benefits our students,’” Quinones says.

One of Espinal’s students came to kindergarten and didn’t speak English. Now she knows all her letters and sounds. “I’m so proud of her,” Espinal says. “She retains things easily.” But then her mind quickly swings to another student, who keeps forgetting her letters, despite Espinal drilling the class daily.

Today, the two are talking about words they can teach students to help model good writing. Quinones has a map of all these words up in her classroom. The two walk out of Espinal’s room and up to the second floor, where the fifth-graders are. This is Quinones’s classroom, where she co-teaches with another teacher. Up near the ceiling are lists of words students can use when talking about comparing, describing, and cause and effect, words like “for example,” “although” and “as opposed to.”

Espinal crosses her arms and looks up at the word map. “Now I’m thinking about all the chances that I could have used those,” she says with a laugh.

“You still have more chances, right?” Quinones replies in a reassuring tone.

From mentor to assistant principal

Quinones remembers how deceivingly hard the role of a kindergarten teacher is. The students test all your boundaries, she said, recalling how she lost 15 pounds that first year.

Quinones grew up traveling back and forth between the Dominican Republic and the Bronx. Her mom was a lawyer, and she remembers watching how hard she worked, a trait Quinones quickly adopted. She wanted to go to school from a young age — and was devastated when her two older siblings would leave for class in the morning while she had to stay behind. In 2005, Quinones started teaching, working at an international school in the Dominican Republic.

“Without support, no one can do this job.” —mentor and fifth-grade teacher Ambar Quinones

In 2012, after she got her certification, she started her first job at a public school in the U.S. in Harlem. She had a mentor teacher, who was provided by the New York City Department of Education, but the mentor teacher wouldn’t follow up on their discussions, Quinones said, so her feedback often felt like a long list of advice without much support.

“The whole year was a very big challenge for me, just knowing what I had to do, which was be a great teacher for those students, and I didn’t know how to,” she says. “Without support, no one can do this job.”

That’s why Quinones started looking for jobs elsewhere. When she heard that Concourse Village was hiring for its first year, she wanted to apply but felt guilty about leaving the students she already had. She applied on one of the last days of the school year and was hired.

She has come a long way since that first year in 2013. In January, Quinones started her role as interim assistant principal at Concourse Village Elementary, making her the first assistant principal in the school’s six-year history. She still has to go through the training and interview process, but she’s already taking on some administrative responsibilities in addition to her teaching duties.

With Sorden’s dramatic success at Concourse, she could conceivably get a job anywhere. But Concourse has also been her dream school, and if she does leave, she doesn’t feel comfortable handing it off to just anyone.

“[Quinones is] a founding member from 2013, and she has an excellent work ethic. She doesn’t take anything personal, which is so important in this job,” Sorden said. “She has those characteristics that a leader needs to have. She has integrity to implement our systems the way they are, and she lives our core values.”

When Sorden first told Quinones she was promoting her, Quinones was both honored and hesitant. Sorden remembers her responding, “Don’t leave me!”

“I said, ‘I’m not leaving just yet!’,” Sorden said. “I’m just trying to foresee the future and think strategically. You have to have a plan in place … it won’t mean anything if I leave and it all falls apart.”

Sorden has always admired Quinones, and by sending her to the New Teacher Center training sessions, she was also preparing her for the leadership role of assistant principal.

Quinones feels that NTC is teaching her how to be a good coach for teachers. The most important thing, she said, is the language she’s learning, of not telling teachers to teach a certain way. It’s like the old adage, she explained: It’s better to teach a man to fish than to give him a fish.

As NTC coaches told Quinones in their first professional learning session last September, mentoring is not about creating a “mini-me.”

“You have to build an autonomous teacher,” Quinones says.

March

When teaching kindergartners, there’s a lot of preparation for when students might get lost. Sometimes literally. Sometimes not.

When Espinal’s students aren’t paying attention one day, she cautions them, “You’re going to get lost if you don’t listen to the directions — you’re going to get lost and you’re not going to know what to do.” That got their attention. “We’re going to get lost?” they shout. “How?”

“I realized you have to be very specific,” Espinal says, laughing.

In today’s meeting with Quinones, the two teachers are talking about just that — anticipating what a student might not know before a lesson and trying to prepare. They are looking at a nonfiction text Espinal might read to them about walruses. Quinones suggests that the students might not know what a walrus is and might confuse it with a seal. So beforehand, Espinal can prepare her students by saying that a walrus looks similar to a seal but is very different.

They also pick vocabulary words to go over before they read the book. But there are a lot: “tusk,” “huddle,” “shoreline.” Perhaps there are some words that the pictures can help explain as they’re reading, Quinones suggests, to save Espinal time having to teach them beforehand.

Finding time to help her mentee can be a challenge for Quinones — one day Espinal couldn’t find Quinones when she needed assistance, so she asked another teacher for advice. It worked out, but the teacher didn’t ask questions like she would have, Quinones recalled, the way New Teacher Center trained her.

Other mentor teachers in the New York City program echo how hard finding time can be. Some of them said they wish their administrators were more on board or understanding of their mentoring positions. But they also remember when they were new teachers and how difficult it was to give up time to go to these sessions.

“I remember the feeling of hatred that I had to give up a prep to go, the inconvenience,” said Shelton, who now mentors four new teachers herself. “But in hindsight, [my mentor] was the one who got me materials to teach with … She recognized qualities in me and stood up for me to the principal. I remember her [telling my principal], ‘You’re lucky to have her,’ and without that, I don’t think I would have been as successful as I was.”

April

For the first time in the New Teacher Center’s history, a new leader took the helm in 2018. Desmond Blackburn was named the CEO after spending three years as superintendent of Brevard Public Schools in Florida. He also worked in Broward County Public Schools, where he rose through the ranks from high school math teacher to chief district administrator.

Blackburn spent the first few months of his tenure on a 10-city listening tour with funders, district partners and mentor teachers to collect feedback on how the New Teacher Center was running. The end of that tour would eventually lead to a shift in the New Teacher Center’s mission statement to focus on equity. Whereas the old mission emphasized improving student learning by improving educator effectiveness, the new mission delves deeper into equity between student groups. Blackburn also named a new executive leadership team this year to carry out that mission.

“The area for opportunity has been for us to really clearly identify what it means to show up for the most systematically underserved children in our country.” —Desmond Blackburn, head of the New Teacher Center

In a phone interview while he was traveling this spring, Blackburn shared that the organization is going to prioritize traditionally underserved students who are most often placed with the most novice teachers, meaning students of color, students with disabilities and English language learners.

“The area for opportunity has been for us to really clearly identify what it means to show up for the most systematically underserved children in our country,” Blackburn said. “While we are proud of the fact that our impact data has been shown to increase student achievement for all kids, we feel it’s important for us to double down and focus attention on those student populations that are not on a trajectory to intersect with the American Dream.”

To do this, the New Teacher Center will be analyzing its curriculum materials as well as exploring what the learning opportunities already are for these student populations. Blackburn took the New Teacher Center leadership team on a trip to Selma, Alabama, to walk across the Edmund Pettis Bridge that Martin Luther King Jr. and hundreds of protesters famously crossed in 1965 and to visit civil rights museums to help understand the history of African-American students.

Recent research has shown that the New Teacher Center is able to increase student achievement in urban schools by several months, but the research was not able to sort out those results by race, gender or disability.

One of the reasons the New Teacher Center has worked so heavily in Bronx schools is because parents there had similar concerns to Blackburn’s: that equity was not at the forefront of their children’s education and that students of color were getting the teachers with the least experience.

These parents were part of the New Settlement Parent Action Committee in District 9. In 2014, they sent a report to newly elected Mayor Bill de Blasio pointing out the educational inequities their children faced. One of the solutions they advocated for was better teacher mentoring, so that their children wouldn’t have four math teachers by the end of November because so few wanted to stay in the building.

The New Teacher Center already had an office in New York City at that point, but when its leaders heard about the Bronx parents’ requests, they created a partnership with them to help support teachers through mentoring and help them form a commitment to District 9 schools. The effort soon expanded to include other Bronx districts, which helped focus NTC’s work in New York City on equity, said Thandi Center, senior director of the New Teacher Center in New York.

Center worked closely with the parents and learned how important it was to them that their teachers not just stick around but be culturally responsive to their students.

“It’s absolutely an equity mission for us.” – Thandi Center, senior director of the New Teacher Center in New York

“When so many of our new teachers are white and English-speaking and so many of our children are black and brown and Spanish-speaking, there’s a huge disconnect in the experience young people have with our teachers,” Center said. “It’s absolutely an equity mission for us.”

Meisha Ross Porter, the executive superintendent of Bronx districts 7-12, said the New Teacher Center mentoring program has helped teachers stay in Bronx schools as well as improve student performance.

“While we have high needs, we also have amazing children that we get to support every day, and they deserve folks who are really committed to them,” Ross Porter said. “So we have a responsibility to provide support so that we can keep people.”

Whether or not mentor teachers receive a stipend or compensation time for their work is dependent on the school, Ross Porter said. Quinones said she does not receive extra compensation for mentoring.

A New Teacher Center analysis found improved retention rates for teachers in Bronx districts 7, 9, 11 and 12 from the 2016-17 to 2017-18 school year — 80 percent of first-year teachers returned to the job, compared with 72 percent of a matched comparison. In District 9, where NTC was able to follow new teachers over the course of three years, 76 percent of NTC-supported teachers returned to their schools, compared with 50 percent of a matched comparison.

May

It’s one of those strange mornings in spring when the sky is nearly cloudless but it is raining. At 7:30 a.m., Quinones and Espinal gather around the desk of the school safety agent, Theresa Howard, who is laughing at the size of Quinones’s backpack. It’s big and gray and probably weighs more than one of Quinones’s fifth-graders.

“Try it on, try it on!” Howard urges Espinal.

“Oh, this is much heavier than my backpack,” she says, handing it back to Quinones.

Quinones laughs, “It’s really not that heavy!” Weight is relative. But the backpack is heavy, stuffed with her computer, student work, and books.

Today, Quinones has her interview for the assistant principal position. The interview is after school at 5 p.m., but she doesn’t have time to be stressed about it. At the end of the day, she’s helping plan a graduation ceremony for her fifth-graders at Columbia University.

When the bell rings, she’s herding students out the door. Then she’s climbing back up the stairs, holding the hands of two students, trying to find their parent. Next she’s bringing two bottles of soda to a classroom for a meeting. But the soda is too warm and there’s no ice, so she brings it back downstairs and hauls up a pack of bottled water. Then she’s back on the first floor, coaching another teacher before they are interrupted by a parent who wants to talk.

“You wanted to see what teachers do? This is what teachers do,” Quinones says, laughing, as she fast-walks down the hall.

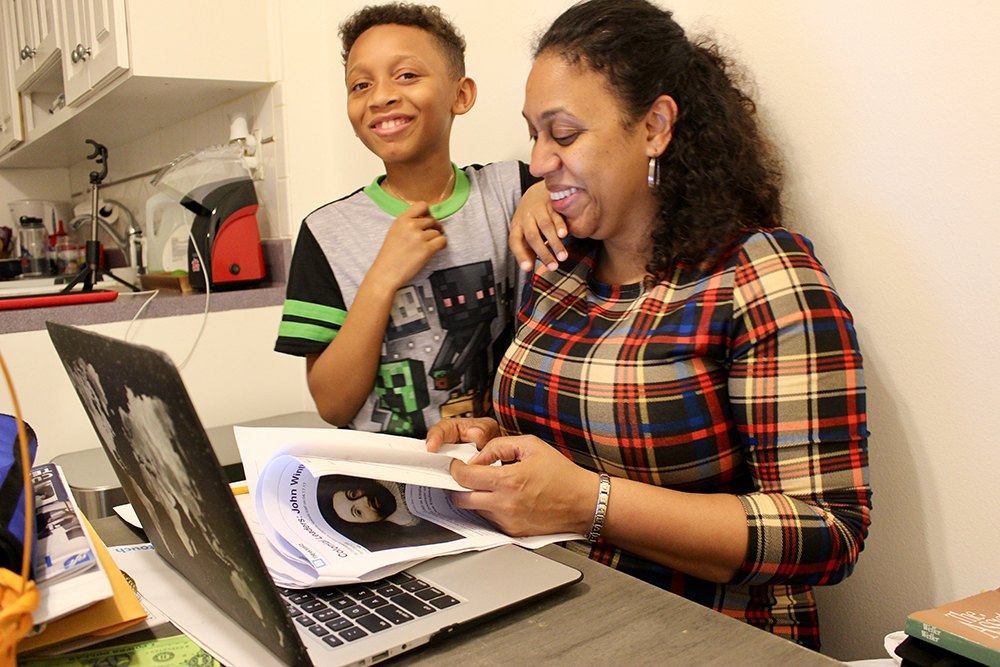

When Quinones gets home, it’s after 7 p.m. She usually orders food for herself and her son, William, who is a fourth-grader at Concourse, because there’s little time to cook. Quinones doesn’t mind staying late at school herself — she’s used to late nights and going eight hours without using the bathroom. But she does worry about making William stay so late. Right now he’s supposed to be doing his homework, but she can hear the TV on in the next room. “I don’t want to be that mom who goes and turns off the TV,” she says, but she shakes her head.

As she washes out the sink, she apologizes for the state of her kitchen table. “I’m probably the only person who has a nice kitchen table and doesn’t eat at it,” she says. It’s piled with books, one titled The Assistant Principal. Her laptop is open and she’s already working.

It will be a few weeks before Quinones receives a letter telling her she’s officially earned the job of assistant principal, the first one at Concourse Village Elementary. For now, Quinones said she can only hope for it because she wants the opportunity to collaborate with other teachers, just as she did with Espinal. But even as an administrator, she wants to remain like Sorden — constantly working in the classrooms to understand what the teachers and students need. She views her role as being like a grandmother to the students. Not directly in charge, but they’re still her kids.

“All the teachers in this school should be on the same page, working for all students, not having inconsistencies in their teaching,” she says. “Principals are coaches. We do what’s right for every student … We are one community. You can’t say, ‘This is not my student.’”

Soon William comes into the kitchen with his homework. “Let me see your annotations,” Quinones says, echoing what she had asked her own students only a few hours earlier. But it’s not up to par for Quinones. “Are you OK with only sometimes doing your best?” she asks. “Then are you OK with the TV only sometimes being on?” It’s a mom power move.

“Go take a shower,” she tells him. He listens, but he calls from the bathroom that she forgot to clean the shower. So she gets up and cleans it and comes back, a glass of water in her hand, ready to keep working. But only a few minutes later, he’s ready to be tucked into bed, so she gets up again.

After William’s bedtime, around 9 p.m., is when she can finally relax, Quinones said, and by relax she means sit on the couch, listen to music and continue doing school work. It’s a nice room to work in — the lights are dim, there’s a big comfy couch, and there’s not too much noise from the street below. William comes out of his room again and leans on her shoulder as she types. It’s not what he’s supposed to be doing, but for now, it’s all right.

‘I love you’

Espinal has two hours before the students will come into her classroom, so she’s bent over a kindergarten table in the little green chair preparing work for them. She eats string cheese and paces back and forth, setting up instructional signs on each table for her reading groups. She’s written the word “look” on a note card and is cutting out each letter for one student who is having trouble with the word.

Right now, all but three of her students are at or surpassing grade level in reading, and Espinal is working intensely with those three to get them up to speed. The students surprise her, though. The one who was struggling with the word “look” has it mastered today. Instead, she’s having trouble with “said.” When Espinal notices, it takes her five seconds to scrap her old plan and make a new one. She tosses out the note cards she spent the morning preparing and pulls out a box of magnetic letters for the student to practice spelling “said.”

Espinal is getting better at giving students independence over their learning. Earlier in the year, she might have hovered and helped students spell out letters, but now she sits back and gives them the chance to do it first.

The students clearly love Espinal. One boy tells her just that as he leaves the building one day. They gather around her as she kneels on the carpet and asks them to share words that end in “–ing”: “getting,” “laughing,” “parking.” They’re so excited, they keep crawling closer to her, so she has to tell them to back up. But she’s calm with the students and has no trouble managing them. “You guys are so good at this,” she says, reaching out her hand to give them high fives.

And the book Espinal thought her kindergartners would never be able to read at the beginning of the year — Judy Blume’s Freckle Juice — they’re reading it. She’s partnered strong readers with weaker ones, and they read the story out loud. They also sit in a circle as a class and read passages together.

“They just emerged,” she says. “I don’t know what happened!”

Her colleagues have noticed that Espinal has emerged too.

“Just last week I was in there and she was so confident, she feels really good about herself,” Sorden said. “She thought she would probably never want to teach kindergarten again, but she’s going to teach it again next year. She’s gained this confidence that she did not have initially.”

Quinones is also impressed by the progress Espinal has made in one year. Whereas she used to go off on tangents during lessons, she focuses now.

“I’m always very proud of her,” Quinones says. She observes Espinal always making improvements based on their last conversations. “I could see that every time I walked in.”

Espinal is still working on taking some time for self-care. Last night, she was working until midnight — “you know how you can get with work,” she says, mimicking typing frantically on a computer. The principal started free yoga after work once a week, and she listens to a yoga app on her morning commute. She and her husband go running at a park near their house and go hiking on the weekend with Macy, their dog.

“I could have gone to schools around where I lived, but I thought, ‘I could have convenience or I could grow,’” Espinal said. “I’m doing this every day; I might as well do a good job.”

Disclosure: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Carnegie Corporation of New York, Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Foundation, and the California Community Foundation provide financial support to New Teacher Center and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter