Greenwich school board chair Peter Sherr can easily tick off the potential cuts that the affluent town will have to make if Connecticut Gov. Dannel Malloy’s proposed budget is approved. Every expense will have to be reexamined, from special education to summer school and afterschool tutoring, he said.

“There will be major cuts to programs,” Sherr said. “It will certainly impact kids very negatively.”

The $20 billion budget Malloy unveiled earlier this month shifts state education funding from suburban and rural communities to poverty-stricken urban school systems, setting up what will likely be a months-long legislative battle.

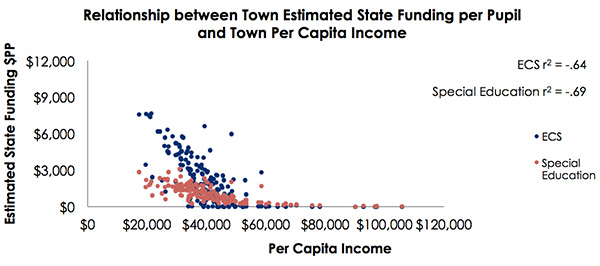

Currently, $2 billion in state school funding is distributed through the Education Cost Sharing formula, which attempts to bridge the difference between the revenue a community generates from property taxes and the actual cost of running its schools. The formula has been underfunded for years.

Malloy proposed decreasing funding to some 130 towns and communities and increasing aid to

30 poorer districts. Many of the suburban communities would effectively get no funding through that formula, policymakers and advocates say.

The state would also change the way it determines poverty, from using a metric defined by students who qualify for free and reduced-price school lunch to one defined by those who qualify for a type of Medicaid known as Husky A.

“The truth is that for too long, we’ve allowed certain communities to be disproportionately impacted by the state’s fiscal challenges,” Malloy said in his budget address. “While we’ve made advancements in recent years to address this inequity, I don’t believe that we’ve gone far enough.”

Under Malloy’s plan, a portion of funding from the Education Cost Sharing formula would be shifted into a fund for special education, which would be prioritized for poorer districts.

“For a city like New Britain, obviously this is great news,” Mayor Erin Stewart told The Connecticut Mirror. “We’re a very poor community, there’s no doubt about that. Our children don’t have a lot.”

New Haven Mayor Toni Harp told the Hartford Courant that she was glad Malloy was finally promoting an "urban educational agenda."

Malloy justified the dramatic shift, in part, by citing the long-running Connecticut Coalition for Justice in Education Funding v. Rell case, in which a judge ruled the state’s school funding system was unfair. The state has appealed, but Malloy praised the judge in his address.

In 2015, the U.S. Department of Education found that Connecticut spent 8.7 percent less per student in its poorest school districts than in its wealthiest during the 2011–12 school year. In Bridgeport, that comes out to $13,883 per student, compared with $20,747 in Greenwich, according to the Connecticut School Finance Project. The average is $15,700 per student.

Still, even advocates for fairer school funding are skeptical of the governor’s proposal.

“Depending on the the way you look at it, it’s either a Robin Hood proposal or a rob-Peter-to-pay-Paul proposal,” said James Finley, principal consultant for the plaintiffs in the Rell case. He said the state should cough up more money for education, not just redistribute it.

Betsy Gara, executive director of the Connecticut Council of Small Towns, told The 74, “I don’t believe it’s fair that some communities are completely zeroed out.”

The Connecticut School Finance Project said the proposal didn’t go far enough.

Malloy has faced a steady stream of criticism from lawmakers, superintendents, and advocacy groups, including the teachers union, which recently released a TV ad criticizing the proposal.

The legislature’s appropriations committee is examining Malloy’s two-year budget plan and has until April 27 to recommend its own.

Beyond the funding issue, a major sticking point is a requirement that municipalities pay one-third of the employer contribution to the cash-strapped state teacher pension fund. Those districts would be paying more and getting less.

Sherr said the school board is talking with other communities to come up with a plan to fight Malloy’s budget.

But Rep. Fred Camillo, who represents Greenwich, doesn’t need to be convinced to oppose the plan. “It is a redistribution of revenue and wealth, and that’s why I will not be voting for it. Plain and simple,” he said.

;)