Every mother wants a better life for her child, and for so many parents across the country education has always represented the key to unlocking America’s promise for the next generation. From pre-k lotteries to Ivy League campuses, education is talked about as “the great equalizer,” aiding children of every socioeconomic background in climbing America’s economic ladder.

But what if your neighborhood school was broken? Broken for years, and generations? So broken that there was little chance it would ever lift your son or daughter, your grandson or granddaughter, to a better place?

In past generations, affluent families coped with such situations by selling their houses and moving in to more expensive districts with better schools or placing their children in expensive, private schools. Working class families sometimes got creative, and used the mailing addresses of nearby relatives or friends to quietly slip their loved ones into better schools a few streets over.

In the 21st century, however, moving kids to the school next door has suddenly become a crime, and an increasing number of parents — often poor, minority, and female — are being arrested and convicted for lying about their address in hopes of rescuing their little ones from dangerous and under-performing schools. In numerous cases, mothers have actually been thrown behind bars for “stealing” an education.

And it’s happening more often than you might think.

Jailed for “stealing” a public education

Consider the case of Tanya McDowell, a Connecticut mother who found herself sentenced to 12 years in jail — a sentence that included both larceny and unrelated drug charges — for enrolling her 5-year-old son A.J. at Norwalk’s

Brookside Elementary School.

According to McDowell, at the time of her arrest, she was not only homeless but had been advised by an individual employed by the Norwalk Board of Education to consider Brookside for A.J. McDowell says she sought guidance from the school board after researching her neighborhood school, the Thomas Hooker School in Bridgeport, and coming to the conclusion that Hooker didn’t meet the academic standards she believed her son deserved.

It is with great pride that McDowell reminisces about how well A.J. did as a youngster enrolled in Connecticut’s Head Start program, and how passionate he was about reading and science at an early age. As a toddler, A.J. declared he would grow up to be either a scientist or a fireman; by kindergarten, he was reading at a third grade level.

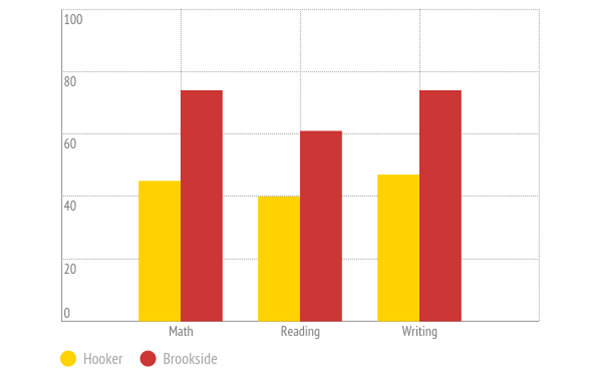

Although only 22 miles separate Brookside and Hooker, the two schools might as well be in different countries. At the time McDowell enrolled A.J. at Brookside, it was academically superior to Hooker by every measure. For example, according to Great Schools.org, which compares schools based upon test scores, in 2011, the year McDowell was arrested, results of the Connecticut Mastery Test (CMT) revealed a wide gulf in student proficiency in reading, writing and math:

Connecticut Mastery Test Results (Percent):

Based upon these academic metrics alone, where would you hope to enroll your child?

Rich Zip Code, Poor Zip Code

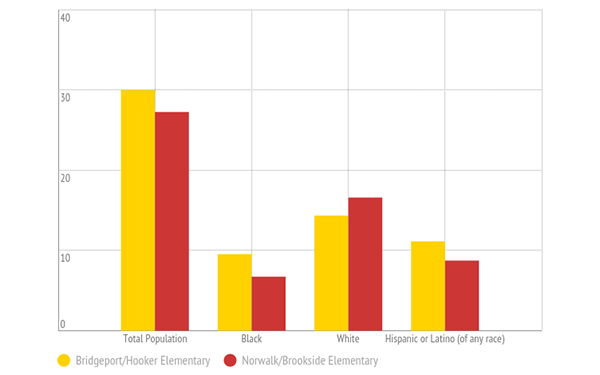

It should come as no surprise that the demographics of the zip codes in which the two schools are located paint a very different picture of what life is like for the children who attend class each day.

Analysis of recent census data paints a portrait of two neighborhoods with black and Latino populations higher than the state average.

School Population (Thousands):

Sources: 2009-2013 American Community Survey of the U.S. Census Bureau

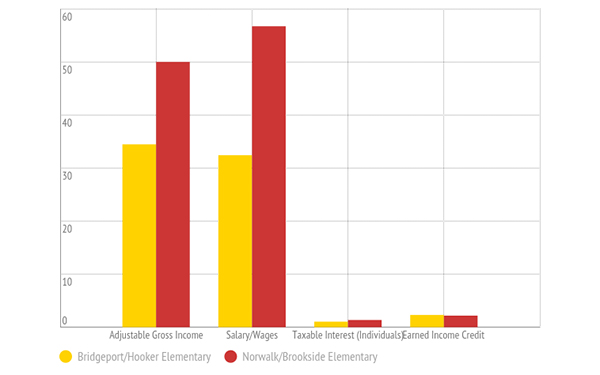

Of greater significance to the quality of the local schools is the highest education level achieved by adults, and the resulting average income.

Income and Program Participation (Dollars in Thousands):

Source: City-Data.com

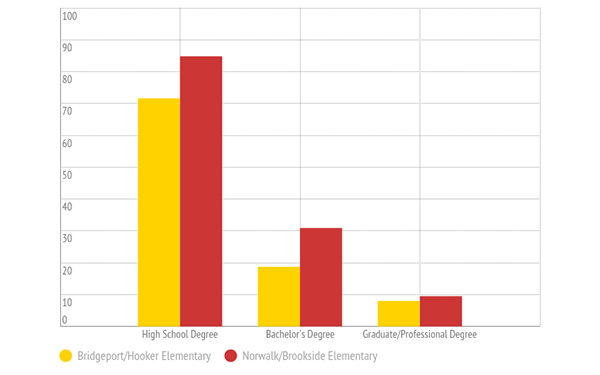

The percentage of the population with a bachelor’s degree, let alone a graduate or professional degree, in the Hooker Elementary zip code is significantly lower than that found in the Brookside zip code. Salaries are also much lower in the Hooker Elementary zip code than in Brookside’s, and the number of third graders proficient in reading, writing, and math is significantly lower in the Hooker Elementary district:

Education for Population 25 Years and Older (Percent):

Tanya McDowell is a first generation, natural born American citizen. She is one of five children; her parents arrived in the United States from Jamaica and Cuba and always expressed a fervent belief that education would be their key to success.

And so when tough economic times hit, leaving McDowell unemployed and homeless, she refused to give up on her son’s education. She found a way to extricate herself from her lease and lower her monthly costs, split her evenings sleeping at various friends’ apartments and drove A.J. every morning to Brookside for kindergarten, where she also routinely volunteered to help with school activities. She swells with pride as she recounts her son’s perfect attendance during her period of homelessness — as well as her volunteering as a cook at the Norwalk Homeless Shelter.

The legal case against McDowell underscores the link between fair housing issues and access to a quality public education. McDowell’s court saga actually originated in a complaint filed by a lawyer with the Norwalk Housing Authority alleging that McDowell had registered her son at Brookside Elementary while living in an apartment in Bridgeport. McDowell denies this allegation and is emphatic that she was in fact homeless.

Following that complaint, and McDowell’s subsequent arrest for “stealing an education,” her case began to garner national attention — and spark national outrage. After McDowell reached out to her uncle, a member of the NAACP, the local chapter rushed to McDowell’s defense and recruited civil rights activist Al Sharpton to speak at an "Equal Education for All" rally held outside Brookside Elementary School.

With civil rights protests heating up, McDowell found her family and her criminal history thrust into the national spotlight. She is the first to admit that she’s made mistakes; it has been reported that over a decade ago, she was convicted of robbing a bank. In another incident, she was sentenced to 18 months in jail for possession of a pistol. And a few months after her initial charges of stealing an education, prosecutors added drug charges, which McDowell’s attorney continues to deny.

As the community started to scrutinize the charges against McDowell as well as her criminal history, some attempted to brand her as a perpetual thief. However, I find these past cases to be largely irrelevant. Do any of these past criminal offenses actually matter, in the context of A.J. and his right to attend a better school? Do prior criminal accusations really mean that her child should be relegated to a sub-par education — or that she should be arrested for trying to give him the tools with which to pursue his dreams of economic mobility?

It was alleged that McDowell stole $15,686 from Norwalk when she enrolled A.J. at Brookside, but presumably because A.J. only attended Brookside for one semester, McDowell was ordered to pay “no more than” $6,200 as restitution to the city of Norwalk. One can imagine that the cost of investigating, prosecuting and incarcerating McDowell cost significantly more than $6,200.

Beyond restitution, McDowell also faced more than 100 years in prison, as her larceny charges were bundled with a trio of drug charges. After accepting a plea offer, McDowell was sentenced to 12 years behind bars, suspended after serving five. Due to good behavior, she was released to a half-way house after completing 3.5 years. She now lives in a resettlement house in Hartford.

Mothers arrested across the country

McDowell’s case might seem like an outlier — a kafkaesque nightmare in which a parent is stripped of her freedom for the sin of wanting to protect and serve her children. But there are other McDowells out there, who have been ripped from their lives and sent to prison for the crime of selecting a school that won’t fail their kids.

In 2011, Kelley Williams-Bolar refused to pay an Ohio school district the $30,000 it demanded when it claimed the mother of two falsified her address and stole an education for her two daughters. She was charged with two counts of records tampering and graft theft, and later sentenced to five years of incarceration on each of the two counts of tampering with records — both third-degree felonies. The presiding judge later suspended the sentence, but Williams-Bolar wound up spending nine days in county jail, and her case sparked a bipartisan outpouring of support from such unlikely allies as the Heartland Institute, the Heritage Foundation, Al Sharpton, Whoopi Goldberg and Sean “P Diddy” Combs. Ohio governor John Kasich was so disturbed by the sentence that he later used his executive clemency authority to reduce the two felonies to two misdemeanors.

Also in 2011, police arrested Myrna Winslow of East St Louis who admitted to forging an occupancy permit and enrolling her son in a high-performing high school, Belleville East. In 2009, Yolanda Hill, a mother of five in Rochester, New York, was charged with two felonies for stealing about $28,000 in education services when she used her mother’s address to enroll her children in a suburban district.

Cases like these are heartbreaking and brutal reminders that public education in the U.S. isn’t really free.

We pay for the “free” public education of our children when we purchase or lease our place of residence; when we find ourselves living in federal or state funded housing for low income families, Section 8 rental housing for very low income families, or even Section 202 senior housing. As a consequence, the cost of a child’s “free” public education is based entirely upon what it costs to live wherever one chooses — or, in some instances, where one is forced to reside. In essence, the cost of a child’s “free” public education is based entirely upon the cost of one’s zip code.

If you are poor and live in a poor zip code, more likely than not, you will find that public education is not free.

If you are working class or underemployed and live in a poor zip code, more likely than not, you will find that public education is not free.

If you are black, Latino, or otherwise a person of color and live in a poor zip code, more likely than not, you will find that public education is not free.

If you are a single mother and live in a poor zip code, more likely than not, you will find that public education is not free.

If you are homeless and have no real zip code, more likely than not, you will find that public education is not free.

Even in 2015, after all the progress that’s been made on other civil rights issues, if you fall into any of these categories, you will find that the hidden cost of your “free” sub-par and mercilessly unequal education is a lost chance at upward economic mobility. When the “free” schools are broken schools, we have abdicated our responsibility to the next generation.

Even worse, if by chance of birth or circumstance you land within a failing district, and make the mistake of seeking out a free public education for your loved ones in a “rich” zip code rather than in your designated “poor” zip code, it might very well cost you your freedom.

It might land you, or your child’s grandparents, in criminal court, charged with a felony, in jail, in prison, or in a half-way house, owing a school district thousands of dollars in restitution as it did Kelley Williams-Bolar of Akron, Ohio, Tanya McDowell of Bridgeport, Connecticut, Myrna Winslow of East St. Louis and Yolanda Hill, of Rochester, New York.

It could cost you partial custody of your child if, like Dorothy Jones of Michigan, you believe that you have no choice but to transfer limited guardianship of your child to a family friend in order to have your child remain in a high performing school.

But there may yet be reason for hope.

In late June, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the application of disparate impact claims under the Fair Housing Act. This means that a claim of discrimination against a defendant can exist based upon the consequences of one’s actions rather than one’s intent if the identified business practice has a disproportionately negative impact on certain groups of individuals and if there is no reasonable, business justification for the practice. Although the Court placed significant restrictions on disparate impact claims, it would appear that the administration of the Fair Housing Act — and possibly our system of education by zip code – may be ripe for a disparate impact claim of some sort.

— With research by Christin Clyburn, Neo Moneri, Arianna Scott and Sofia Williamson

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)