Solving the Rural Education Gap: Experts Weigh In on New Report’s Findings Tying Gap to Prosperity

Whether these students end up graduating from high school and college, and how they fare in the workforce, is linked inextricably to their rural education experiences, a new report finds.

The study, published in April by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service, sheds light on the state of rural education and its relationship to economic prosperity in regions of the country that played a pivotal part in President Donald Trump’s election.

Among the notable findings:

- While rural Americans are increasingly better educated, those who are older, male, and minority still lag behind their urban counterparts in levels of educational attainment.

- Rural women are increasingly better educated than rural men, with women holding a greater share of degrees at every level.

- Rural counties, such as in Appalachia and the Mississippi Delta, where individuals have the lowest levels of educational attainment struggle with higher overall poverty, child poverty, unemployment, and population loss than other rural counties.

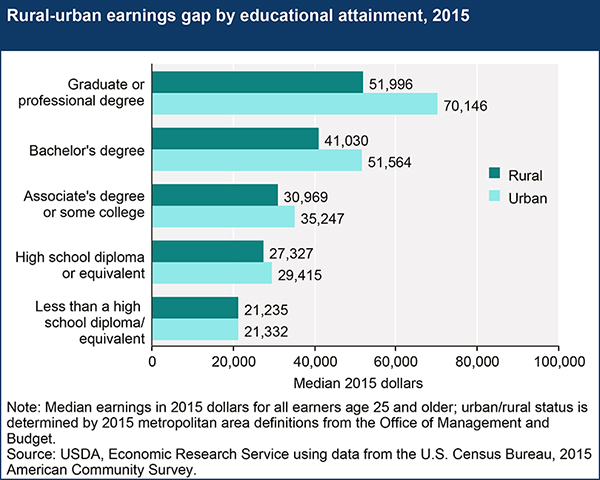

“Median earnings rise with educational attainment in both rural and urban areas … [but] in 2015, median earnings in rural areas were a fraction of those in urban areas for every level of education, with a larger earnings gap at higher levels of education,’’ Alexander Marré, a research agricultural economist at the Department of Agriculture, says in his report.

The challenges of rural education and the lack of opportunity in those parts of the country have been in the spotlight since the presidential election, when many working-class voters expressed hopes that Trump, a New York City real estate developer who declared his love for the “poorly educated,” would help revive stagnating rural communities by, for example, deregulating the coal industry and bringing back mining jobs. In that vein, Trump on Thursday announced plans to back out of the Paris climate accord, making good on a campaign promise to coal country and energy-dependent states in the West.

But meeting the unique needs of rural students in an uncertain political and economic environment is its own issue. Below, we highlight the report’s findings and ask a few experts to consider the task ahead for policymakers.

The rural-urban gap in college completion is widening.

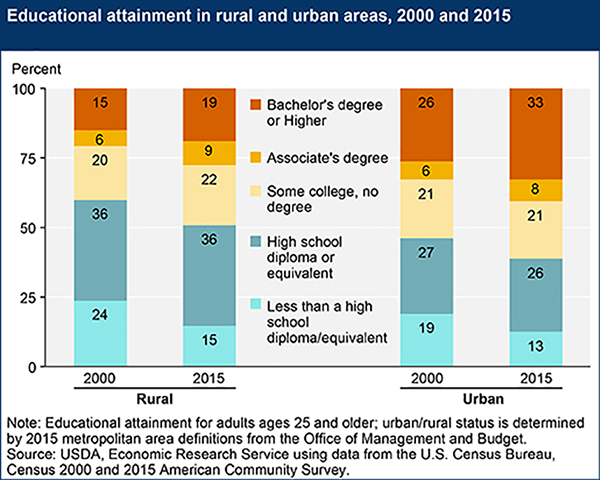

Between 2000 and 2015, the share of urban adults with at least a bachelor’s degree jumped from 26 percent to 33 percent, while the share in rural areas grew from 15 percent to 19 percent, according to the report, which is based on data from the the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey and other federal sources. One reason for the growing gap may be higher pay offered to workers with college degrees in urban areas; another may be the fact that some rural students leave their hometowns, choosing to attend college in more populated areas, and take advantage of better urban job markets after graduation, the report states.

Catharine Biddle, an assistant professor of educational leadership at the University of Maine, said she wasn’t at all surprised by the data.

Looking at the macro-level economic picture, she explained, urban areas “are great if you want to have people working in highly specialized fields and collaborating in dense networks.” But rural areas have traditionally been structured very differently, in ways that provide resources to urban areas and support the larger economy.

“Over the last couple of decades, we’ve seen more automation and more companies choosing to take their work overseas, so you see fewer and fewer industries in those areas,” Biddle said.

Industries that persist in the U.S. still offer fewer jobs, and historically those jobs haven’t required college-level education to make a living wage, she added.

Since 2000, rural Americans have become increasingly better educated, with the majority of adults now holding at least a high school diploma, compared with the 56 percent of rural adults over age 25 who did not hold a high school diploma in 1970. However, certain demographic groups are lagging behind.

In rural areas, racial and ethnic minorities, men, and older individuals are less likely to have a bachelor’s degree than their white, female, and younger counterparts. For example, while the share of high school dropouts among rural Hispanics or Latinos fell from just more than half to 39 percent between 2000 and 2015, the report finds, racial and ethnic minorities comprise an increasing share of the rural population without a high school diploma.

Rural women outpaced rural men in obtaining all types of degrees, including high school diplomas, associate’s degrees, and bachelor’s degrees, between 2000 and 2015. The share of rural women with bachelor’s degrees or higher grew by 5 percentage points, compared with 3 percentage points for rural men, according to the report.

Biddle surmised that women have been earning college degrees in greater numbers than men for a long time, particularly in rural areas.

“Women are getting college degrees in greater numbers regardless of where you are, but in rural areas I think that’s always been the case,” she said. “Women have seen education as more fruitful and full of opportunity for them because the industries that exist in rural areas [such as coal mining or natural gas drilling, which typically don’t require a college degree] are [often] very gendered."

The gender divide around college may be related to a resistance among some men to uproot themselves or their families in rural communities where geographic place is often closely associated with identity for generations of people, mused Allen Pratt, the executive director of the National Rural Education Association based in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

“Going to college is actually a major commitment to leave … and go somewhere else,” said Pratt, a former high school science teacher and administrator. “A lot of males don’t want to leave; they want to stay and work and raise a family and do what they need to do.”

Expanding opportunities for women in the workforce compared with those in decades past is also likely a factor in the greater numbers of women completing college, he said.

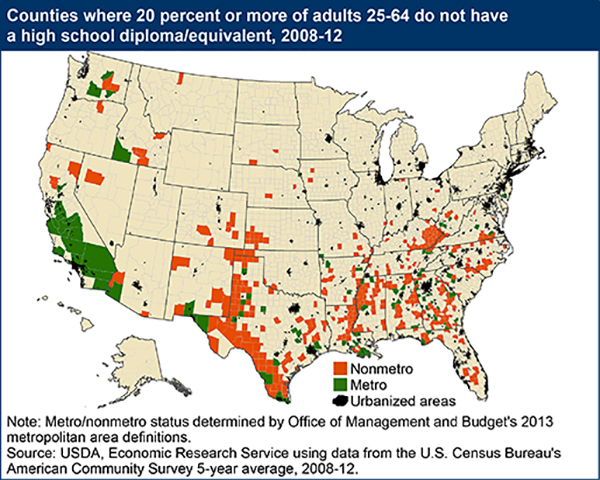

Rural counties with low levels of educational attainment have worse economic outcomes. Educational attainment levels are lowest in the rural South, where clusters of persistently high-poverty counties include Appalachia, the Mississippi Delta, and communities along the Texas-Mexico border. Higher poverty in the South is both a cause and consequence of lower educational attainment.

Pratt, of the National Rural Education Association, said inequitable school funding to rural districts and the greater political influence of non-rural education advocates — because of their sheer size — contributes to furthering inequity.

“It’s always a battle where we try to promote that [rural district] voice and that unified front,” he said. “It’s a numbers game.”

(The 74: New Study Finds States Fail to Deliver on Title I Promise of Extra Funding for Low-Income Students)

One solution, he suggests, is re-aligning K-12 curricula to better meet changing workforce needs in rural areas, creating incentives for young people to stay and contribute to their region after graduation. Expanding vocational training programs is vital, Pratt said, pointing to one such program started in 2014 in Chester County, Tennessee, where students graduate from high school with a certification in advanced manufacturing, one of the state’s top industries.

Biddle, the professor in Bangor, the third-largest city in Maine, with about 33,000 residents, agreed that it’s long past time for reconfiguring what’s offered in rural districts to what is needed in the workplace.

Education in rural places is “complicit in the systems that are making it difficult for people to live sustainably in rural communities today,” she said.

Jobs in mills as well as the fishing and timber industries are still available, Biddle said, and “there’s still some feeling of nostalgia [in rural communities] like ‘Maybe we can make this work.’ ”

“I think there’s this feeling of ‘Well, maybe my kids can still get in before this [industry or career path] becomes totally unviable,’ ” Biddle said, “and I think schools are really pushing back against this and having to say, a college degree is the best way we know right now to guarantee that your child will be able to adapt to the uncertain economic future that I think we’re all struggling with in this country.’ ”

Educators need support in getting that message across to parents and encouraging families to start saving for college early, she said.

But schools alone can’t solve this complex problem.

At the heart of the issue is spurring economic development in rural areas — a large-scale policy challenge that will require business leaders, elected representatives, educators, and families to work together, Biddle said.

“Policymakers have not given traditionally rural areas a great deal of thought when they’re putting policies together,” she said. “There’s been this kind of laissez-faire attitude to these areas, and I think there is a feeling, at least within the communities that I’ve worked in, that without those supports, it’s hard to figure out how to move forward.”

The Trump administration’s education agenda is built on expanding school choice through a proposed $250 million private school voucher program and investing $1 billion in districts that allow dollars to follow students as they transfer among public schools (a practice known as portability), while seriously slashing overall federal education spending by $9 billion. What role can these initiatives play in improving educational opportunities for K-12 students in rural schools?

Rural public education experts like Biddle and Pratt tend to resist vouchers, noting that there are fewer district school alternatives in rural regions for students to choose from. When students do leave the district schools, they argue, state per-pupil funding follows them to a charter school or private school, and those losses can cripple already-strained district budgets.

“Any kind of voucher system becomes really hard for a rural school system to sustain,” Biddle said. Although open enrollment and competition between public schools are something principals and district superintendents “are learning how to manage,” she said, “the idea that that competition would be opened up to any type of school … becomes really complex,” especially when it comes to meeting the special needs of students with disabilities, who wouldn’t necessarily be guaranteed special services.

But Ron Matus, director of policy and public affairs for Step Up for Students, is more optimistic, based on the results of the Florida tax credit scholarship program and an education savings account that his organization administers. The organization has awarded scholarships to more than 105,000 students this year, including children with disabilities, to pay tuition for private schools and obtain special services as well as transportation to public schools outside of their district.

Matus said in an email that while he doesn’t know of studies that examine academic outcomes for non-district schools in rural areas, his experience in Florida “leads me to question this solidifying narrative that private school choice can’t work in the boonies.”

“In Florida, we not only have a fair number of private schools in the hinterlands … but thanks to Florida’s robust array of private and virtual school options, we see these schools growing and new ones cropping up,” he said. “School choice isn’t a silver bullet, but to the extent that more options can bring more opportunities for more parents to put their kids on a surer path to success, I think there’s plenty of potential for that to happen in rural areas too.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)