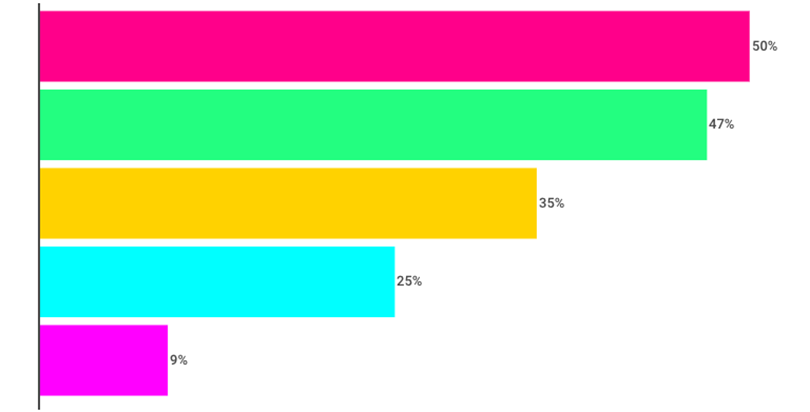

Raw Numbers: Charter Students Are Graduating From College at Three to Five Times the National Average

Charter schools primarily serve low-income, minority students. Across nine of the country’s largest charter networks, college graduation rates range from 25 percent to 50 percent, according to the first-ever reported data in the new Richard Whitmire series “The Alumni.” Nationwide, just 9 percent of students from low-income families earn bachelor’s degrees within six years. (That figure rises slightly — to 15 percent — when the sample eliminates those who drop out of K-12, narrowing the pool to students from low-income families who graduate high school first.)

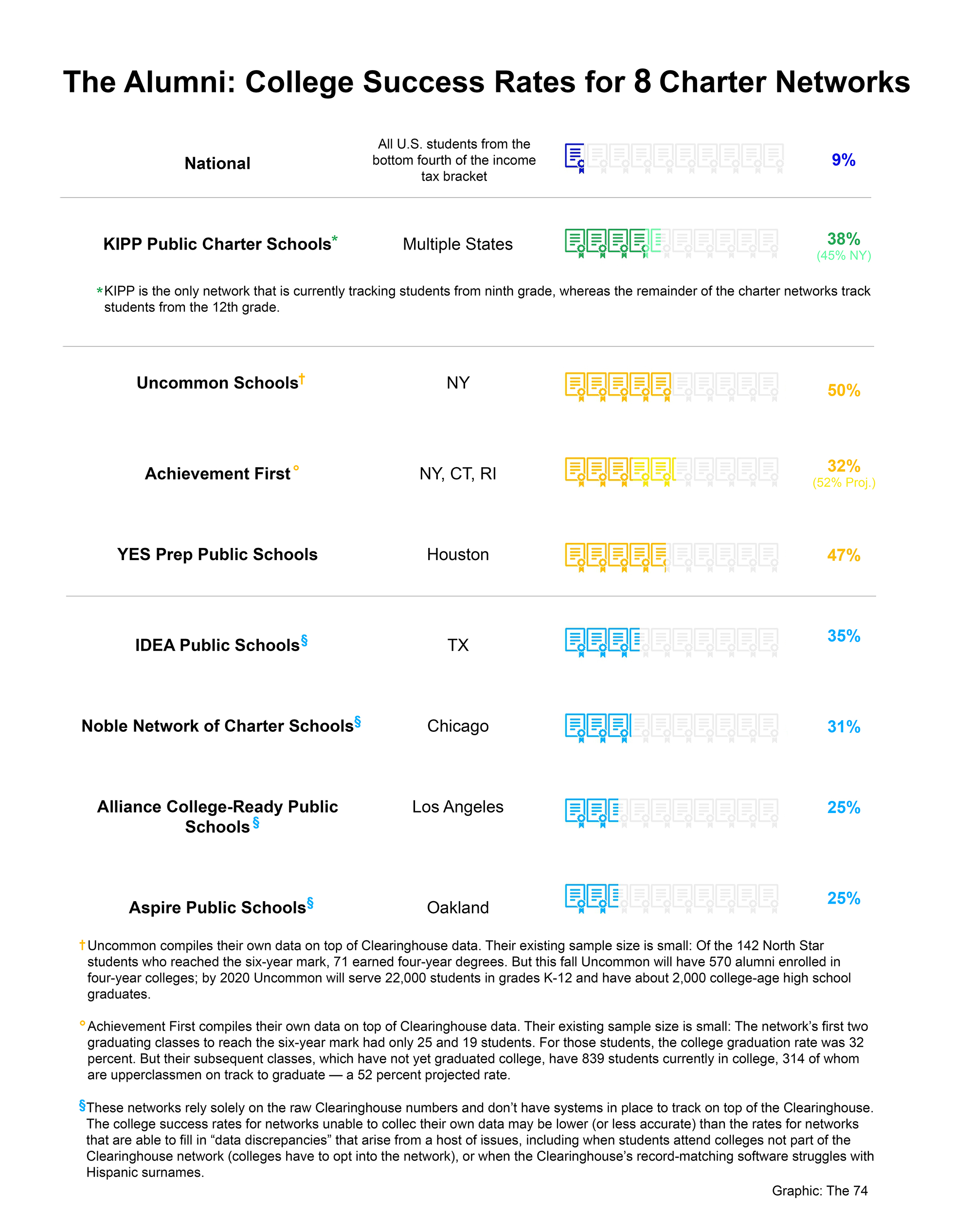

Here are the new numbers for eight leading networks; take note of the different ways in which students are being tracked:

The first charter school opened its doors in St. Paul, Minn., in 1992. At the time, faculty members of the newly established City Academy sought referrals from the district and recruited students from city streets. A quarter of the school’s inaugural class of about 35 was homeless.

Now, 25 years later, more than 6,700 charter schools are serving nearly 3 million students — 6 percent of all public school students in America — across 43 states and Washington, D.C. The National Alliance for Public Charter Schools expects those figures to grow to 10,000 schools and 4 million students by 2020.

As Whitmire writes about in “The Alumni,” if the majority of these schools now begin tracking their students into college, and judging success based solely on how many complete college, it would be noteworthy — and potentially revolutionary.

“In years past, K-12 accountability measures focused on data points such as third-grade reading scores, the number of ninth-graders taking algebra, or setting new records for the most number of AP tests taken and passed,” he writes. “My prediction: Those data points will remain markers but will be subsumed by the far larger data point of college completion. Like it or not, college is the new high school, regardless of the chosen career. Who doesn’t need to be a careful reader and writer to work in sophisticated blue-collar jobs? We need to judge high schools by how many of their graduates earn college degrees within six years.”

“While charter leaders don’t want to stir up more controversy by saying it out loud, the implication is clear: Traditional high schools need to get on board with the same goal. Again, college is the new high school. And that rule applies equally to low-income minority students, who make up half the student bodies of our nation’s public schools.”

Visit TheAlumni.The74Million.org for a full network-by-network explanation of the college data, as well as a host of additional feature articles, essay, video documentaries, and student testimonials that explain in depth this new campaign at many of America’s best public schools.

A few caveats exist with the reporting:

-

The meat of the data come from the National Student Clearinghouse, which matches high school, college, and other identifier records to track students as they progress through higher education. The charter networks purchase the data from the Clearinghouse, and colleges must opt in to the Clearinghouse network. To account for gaps in the Clearinghouse data (like failure to match names, student privacy requests, and students attending non–Clearinghouse network colleges), some charter networks also use their own systems to keep track of every student. Others networks don’t have these systems and use only Clearinghouse data.

-

The networks that rely solely on Clearinghouse data may see rates a few percentage points lower (or just less accurate) than their actual rate of success because they are unable to account for those data discrepancies.

-

KIPP is the only network that tracks its students beginning in the ninth grade, meaning that their college graduation rates may appear lower because they account for students who drop out of high school. All the other networks track students beginning in 12th grade, and thus have sliced off the segment of students who leave the system before high school graduation.

-

Because charter schools are so new and they are just beginning to graduate their first classes of college students, some sample sizes (like those of Uncommon Schools and Achievement First) are small. Those networks have hundreds currently in college, and they will round out the data as those students graduate in the coming years.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)