Personalized Learning for Every Student: How 2 Very Different School Systems Pursued a District-Wide Strategy

By definition, personalized learning is idiosyncratic, and common wisdom has held that because of their flexibility, public charter schools have the advantage when it comes to using technology as a tool to engage each student according to their passions. School districts, the supposition has been, are too rigid to easily enable truly individualized learning.

A RAND Corp. study released earlier this week came to no firm conclusion on this point, though it jibed with past reports on the elements and school settings in which personalized learning seems to flourish. With this in mind, the study’s authors suggested that anyone hoping to take a look at early, district-wide implementation turn to three distinct school systems: Piedmont, Alabama; Georgia’s Fulton County; and Horry County, South Carolina.

(The 74: Personalized Learning Boosts Math Scores, New RAND Study Finds — But Scaling Is a Challenge)

In suburban Atlanta, Fulton County Schools rolled out not one but 94 models, customizing personalized learning for each of its schools. District leaders announced they had funds to buy a device for every student but said each school had to come up with a plan for using them that started with the end in mind.

Piedmont and Horry County are home to individual schools examined in the study, which compared 40 schools that received Next Generation Learning Challenge (NGLC) grants. A partnership of a number of organizations, NGLC was funded primarily by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which engaged RAND to compare the grantees to traditional schools with similar student demographics.

The districts named in the new report were impressed enough with their initial forays into personalized learning to implement the model as widely as possible. Their leaders say they were quick to see results, albeit after very different early experiences with the approach.

When Piedmont City Schools decided to buy all 1,240 of its students laptops or tablets, the goal wasn’t to increase achievement. The hope was to revive the community, located in the Appalachian foothills in northeast Alabama. Over the past two decades, 4,000 textile jobs disappeared from the region, and families were following.

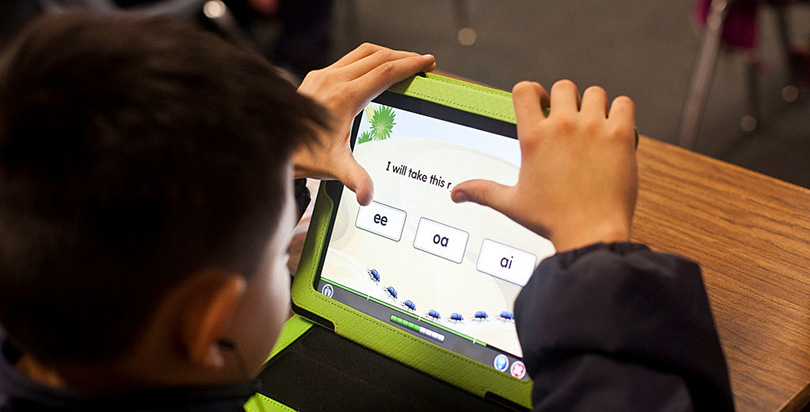

In 2009, with an eye to connecting the 4,800 remaining residents to the outside world, the school district gave every student a device: MacBooks for older kids and iPads for younger pupils. Piedmont is too small to offer the same array of subjects as a large district, but the technology allowed students to venture online for challenges such as foreign language classes or applied physics.

It wasn’t until after the technology was purchased that the superintendent, out driving one night, noticed a bunch of students clustered outside the school doing their homework in the building’s Wi-Fi bubble. Just 60 percent of Alabama households have internet access, 13 points less than the national rate, and many families couldn’t afford it if existed. So the district built a network covering the whole town.

The technology yielded so many unforeseen benefits that when the state’s superintendent of education raised the topic of a cutting-edge education innovation known as personalized learning, 80 percent of Piedmont’s teachers demanded to see it in action. Three years ago, they upended the concept of class at the middle school.

Students now use their laptops to work at their own pace, moving ahead not when their class does or their grade changes but when they can demonstrate they’ve mastered a skill. Teachers do less instructing and more coaching. The shift worked so well, Piedmont has extended the model to all three of its schools.

Test scores are up and students are pushing themselves, says Jerry Snow, principal of the middle school and a leader of the initiative: “We have kids graduating from high school with two-year [community college] degrees.”

Indeed, Piedmont’s experience might be described as textbook disruptive innovation: the unexpected leaps that happen when the arrival of technology births possibilities people could not previously imagine. In the case of K-12 education, that means anything from allowing a single teacher to tailor lessons both for pupils missing skills and high-flyers to giving students a goal and allowing them to decide, with educator support, how to meet it.

Results released by RAND on Tuesday build on a larger survey released by the same researchers in 2015 that found that personalized learning schools achieve significant gains in student growth. The new research is more limited in scope and its findings more modest than past comparisons between schools using personalized learning and their traditional counterparts. Researchers considered academic outcomes but focused more on how schools were implementing personalized learning and which elements educators were embracing.

As it happens, both Piedmont and Horry County report success with some things RAND raised as weaknesses in the new study. Broadly sketched, both school systems have been able to assign district-level staff to take over personalization’s time-consuming aspects.

Teachers in the NGLC schools told the researchers that finding a variety of high-quality curricula for students to choose from was a problem. Further complicating this was the difficulty of making sure those options covered content in a way that aligned with states’ standards for what students should know. Both districts surpassed this hurdle by assigning the task to district staff who are on standby to fulfill teacher requests.

“Creating ‘playlists,’ aligning lessons with standards — those things are the appropriate role of the district in public education,” says Lars Esdal, executive director of Education Evolving, a Minnesota-based nonprofit focused on innovation in schools. “The biggie is the curriculum and instruction model: Is it able to be adapted to individual schools and teachers?”

Horry County, South Carolina

South Carolina’s third-largest district, Horry County dwarfs Piedmont, with more than 42,000 students. Its introduction to personalized learning was launched by a principal brought in to turn around Whittemore Park Middle School, where 85 percent of students come from low-income families. By the end of the effort’s first year, the school’s students were outperforming district averages by more than 10 percentage points.

Horry County’s 3,000 teachers are embracing the change at differing paces, says the district’s digital communications coordinator, Ashley Gasperson. “You have those who are on the cutting edge who are trying things on their own,” she says. “And you have teachers who have been doing things their way for years with good results who are reluctant to rock the boat.”

District staff eliminated one major source of anxiety by handing the technology to teachers months before they were expected to use it and by planning, down to the location and amperage of power supplies, how devices would be handled.

“The structural shift happened relatively quickly,” says Gasperson, “but the philosophical shift is ongoing.”

That philosophical shift is the move from seeing personalized learning as a system that relies on technology to one in which students are given maximum agency. Results of the current report and its predecessors suggest that schools that give students more power are likely to see greater achievement, both in academics and in terms of persistence, critical inquiry skills, and other traits that prepare students for college and careers.

“Kids are not afraid of technology,” she says. “The adults are the ones who are apprehensive. Because it’s a learning curve. You can relinquish control — the kids understand the technology.”

In fact, kids dove into the possibilities unleashed by the devices so enthusiastically that over eight years, participation in a district technology fair — at which students exhibit their high-tech works — mushroomed from 350 to more than 3,000 students.

“This year we had 53 students age 6 or younger,” says Gasperson. “We had preschoolers who were showing their digital photography talking with kids 10 years older who were doing the same thing.”

Lead RAND researcher John Pane cautions that much more research needs to be conducted for any broad, declarative statements. In the meantime, however, he’s optimistic.

So is Piedmont’s Snow, who notes that one of the hallmarks of all that technology is the information it can provide to both teachers and students. Three years in, his schools are continually refining.

“It’s easy to stand in front of a class and tell [students] things,” says Snow. “What’s hard is to be working with kids who are in all different places. It’s difficult, but we think it’s what’s best for kids.”

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation provides funding to The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)