Denisha Merriweather, in Her Own Words: The Private School Scholarship That Changed My Life

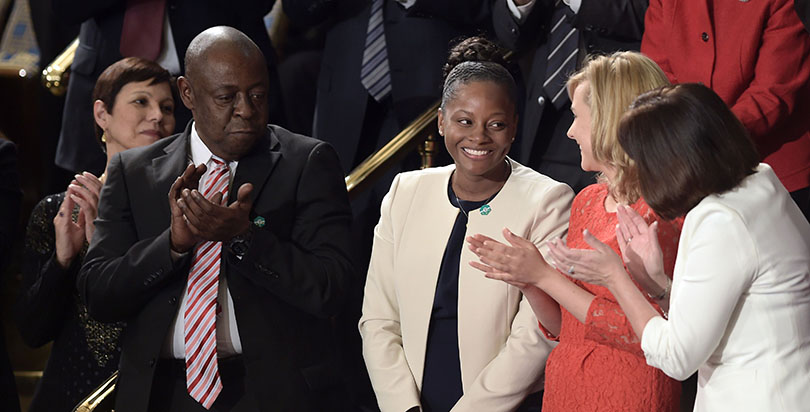

When President Trump gives his first address to Congress tonight, he’s likely to introduce the nation to an invited graduate student: Denisha Merriweather, a master’s candidate at the University of South Florida studying social work. A beneficiary of the Florida tax credit scholarship, Merriweather has long advocated for school choice legislation, arguing that other students should have access to the same opportunities and choices that she enjoyed.

The state's tax credit scholarship program is now in its 15th year and serves nearly 100,000 low-income students by allowing them to use funds for private schooling that come from donations given by corporations in exchange for tax breaks. The program has now withstood multi-year legal challenges from the state’s teachers union and a local branch of the NAACP, who argued that the tax credits took money away from public schools. Multiple courts declined to hear their case because the plaintiffs couldn’t prove that they had personally been injured by the scholarship.

Last month, the state Supreme Court ended this long judicial appeal process when it too declined to hear the case, allowing the scholarship program to stand.

74 Video: What’s a Tax Credit Scholarship?

Many expect the president to use Tuesday’s address to resurface plans to prioritize funding for school choice initiatives. Merriweather’s personal success story will no doubt be held up as an example of why the administration wants to offer more families more options in educating their children.

Merriweather penned an essay for The 74 last month, in which she explained how transferring schools changed everything about her life, leaving her more motivated, empowered, and confident that she’d be able to achieve her goals. Here's Denisha’s story in her own words:

I grew up in Jacksonville, Fla., mostly on the Eastside. My old neighborhood sits along the St. Johns River, just east of downtown. It’s near EverBank Field, where the Jaguars play. It was once a haven for black families during the time of segregation. The community thrived, with black-owned businesses and spontaneous cookouts. In the years before I was born, drugs and alcohol infiltrated the community. Crime rates soared. Drug abusers and police interventions became normal sights. The Eastside became a place people avoided at night.

The Eastside has become the focus of many urban projects in the City of Jacksonville, but statistics tell a sad tale. The median household income in the ZIP code where I grew up is about half the citywide average. According to the latest U.S. Census Bureau data, 41 percent of Eastside residents receive food stamps, compared with 16 percent of Jacksonville residents overall.

Now that I’m in graduate school, I can look up statistics that suggest I’ve beaten the odds. I’ve read about the studies showing that students who don’t read proficiently by the third grade are four times as likely to drop out of high school as those who do, and those in poverty are 13 times less likely to graduate on time than their more proficient, wealthier peers.

That was me. I failed third grade — twice.

I’ve written many times about how a school choice scholarship helped me turn my academics around and escape the pull of generational poverty. But as I work toward a master’s degree in social work and reflect on my experiences, I’ve come to understand how multiple community institutions helped me get where I am today.

The Eastside is full of abandoned homes and stores. People walk the neighborhood aimlessly with seemingly little hope. There are three zoned schools for the neighborhood, which were underperforming when I attended and still are, despite the best efforts of Duval County Public Schools. There are few real school options on the Eastside, though there are some in other surrounding neighborhoods. There are hardly any job opportunities for adults, and it feels like there is no way out for many who live there.

People from the Eastside know one another by name. Community members proudly chant “Eastside” while throwing up a hand symbol representing the letter E. Gatekeepers, or those who maintain Eastside culture, claim “status” if their family name is chanted in the same manner.

It seemed the Merriweathers had status. My family had lived in poverty for at least four generations in the same place, which isn’t uncommon on the Eastside. My relatives had earned a reputation for defending their own.

While the name may have protected me in the neighborhood, it also followed me into the classroom. One adult at school might turn to another and say, “She’s a Merriweather.” The name seemed to justify my behavior and hold me to a stereotype. Many teachers on the Eastside had been around a long time. I guess some of them assumed I was destined to drop out of school as a teenager, like my mom and her brother.

The earliest memory I have of school was in the second grade. I remember being puzzled and angry because I didn’t understand the lessons being taught. I remember wanting to ask my teacher to repeat herself, but I got the sense that she didn’t want to help me understand. I feared being ridiculed by the other students. My classmates were very critical. I did my best to just fit in.

It was during that time I began to hate school. The next couple of years felt like I was in a daze. Things at home were unstable. The time I spent with my biological mother was often in a Jacksonville hotel room. We moved more than five times over the next few years.

With every move, I’d wind up in a different school. With every new school, I had to meet new teachers, administrators, and classmates. I never expected to stay in one school for very long, so I often assumed the rules didn’t apply to me.

I remember days when I would walk into the classroom and everyone would sigh, including my teacher.

I grew disheartened. To hide my hurt, I often lashed out in physical fights with my classmates. The principal’s office became my new classroom, and I got used to being suspended. D’s and F’s filled my report cards.

Despite my facade, I wanted to learn, to be accepted, happy, and motivated.

In fourth grade, I had a gleam of hope. I was admitted into the school district’s STAR program. Its name stands for Students Taking Academic Responsibility, and it’s designed to help students get back to grade level. I was told the program was competitive and that if I behaved and got my grades up, I could be promoted to middle school, with other students my age.

I started writing myself letters in the voices of teachers, who reprimanded me: “Denisha, don’t talk today.” “Be good.” “No playing in class.” “Come on, you can do it.” I wanted to beat the teacher to it.

At the end of the year, I received notification that I wouldn’t be promoted to middle school. That news wrecked my self-esteem. But the summer before my sixth-grade year, the trajectory of my life began to change. I began living permanently with my godmother. We moved into a Habitat for Humanity home. She enrolled me at Esprit de Corps Center for Learning, a small, private school on the Northside of Jacksonville, using a Step Up for Students tax credit scholarship.

Now my life had something it hadn’t had before: stability. I had my own room at home, which provided me a place of solace. I didn’t have to change schools anymore. Living with my godmother didn’t separate me completely from my life on the Eastside. But she had a job at a Brooks Rehabilitation facility, made an honest wage, and set a good example for me.

Esprit de Corps is affiliated with the church I attended with my godmother. On the first day of school, I was racked with nervousness and embarrassment. I decided I was ready to defend myself no matter the cost. I didn’t know what to expect. I knew some students from church, and I was anxious because I thought they’d find out I was dumb. However, to my surprise, I never had to defend myself or my intellect. Esprit de Corps was unlike any school I’d ever experienced.

We had chapel every Tuesday and assembly every Friday. The faith-based environment taught me that God was interested in all my actions. I gradually gained confidence and consistently made the honor roll. I joined the basketball team, served in student government, and participated on the yearbook committee. Administrators chose me to become a cadet — a designation reserved for student leaders who wear red sweaters and help out on campus. It seemed like I finally had a normal life.

Before coming to live with my godmother, I’d play with friends in the neighborhood after school or watch television without doing my homework or preparing for the next day of school. My godmother enrolled me in an after-school program at the Police Athletic League on Jacksonville’s Northside. PAL provided me with structure after school. We had times for activities, homework, a snack, and dinner.

Some 19 percent of juvenile crimes occur between 3 and 7 p.m. on school days, according to the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. A study done in Chicago found that low-income students who participated in after-school programs increased academic performance, saw misconduct decrease, and were more likely to graduate from high school. Also, low-income students who became involved in after-school activities saw an increase in motivation and hope.

One day at PAL, I was approached by a woman whom I now call my mentor. She invited me to participate in a leadership program called the Youth Directors Council, which helped organize community service events. The program taught me to take responsibility for my actions because my grades, community service involvement, and leadership skills all helped determine who got to go to Disney World during the summer, which was the program’s annual highlight.

Regional, state, and national meetings connected me with PAL students across the country. Through my community service work, I earned the award of National PAL Girl of the Year in 2009. I was suddenly surrounded with people who pushed me to look beyond the world I was familiar with, beyond the Eastside of Jacksonville.

As I got older, I enrolled at my local community college to take dual enrollment classes. My school had become a major support system. When it was time for me to apply for college, Esprit helped me research scholarships and apply for waivers to take my college entrance tests for free. On June 5, 2010, I graduated from Esprit de Corps with honors, becoming the first in my immediate family to earn a diploma. I resolved that I would go on to pursue every degree I could.

Education allowed me to create a new path for my future. A healthy school culture gave me the strength and courage I needed to embrace my new life and develop goals for my future. There are many paths to escape the dead end into which many students like me are born.

I was given the opportunity to attend a private Christian school on a tax credit scholarship. Some find their way using traditional public schools. In Duval County, a growing number of parents are choosing to teach their children at home. The year after I graduated, a new KIPP charter school opened on the Northside, and though it’s at least a 15-minute drive for parents on the Eastside, it provides a new option for low-income students in the city.

I believe all these venues and more need to be accessible to kids growing up in poverty, who need more high-quality school options. But I also believe they need healthy community support, stable home environments, and individuals who can serve as mentors.

Too often, the education system views black children, their community, and its challenges through a deficit-based perspective that emphasizes their alleged shortcomings inside and outside the classroom.

I want the beneficiaries of school choice to advocate for a strengths-based perspective that focuses on the potential of every child and that ensures schools and other community institutions marshal the resources necessary to help them achieve it, while considering the interrelationships between individuals and their environments. In my graduate studies, I have learned about the concept of person-in-environment, which is the guiding principle of social work. It means that in order to totally understand a person, you have to understand the environment they come from and tailor services based on that knowledge.

I hope to see all schools serving children in poverty embrace a wraparound model, providing not only education but also health, social, dental, and other community services such as after-school programs. Families should be able to customize these resources for their children, the way my godmother did for me.

As I’ve gotten more involved in education reform advocacy, I’ve seen many people who advocate for more educational options like the scholarship I received. But I’ve also seen a separate political tribe that argues against those options. It’s frustrating to me that there are still groups who are fighting to end tax credit scholarships, which would effectively kick out nearly 98,000 low-income students in Florida, including my younger brothers and sisters, from the private schools that work for them. Those same groups then turn around and argue that we should create community schools instead, as if these private schools are not grounded in their local communities.

I’m confident that if these groups would stop and listen to the thousands of school-choice alumni like me, they would learn that if we truly care about breaking the cycle of generational poverty, we need all hands on deck. We can’t afford to take any options off the table.

The Dick & Betsy DeVos Family Foundation provided funding to The 74 from 2014 to 2016. Campbell Brown serves on the boards of both The 74 and the American Federation for Children, which was formerly chaired by Betsy DeVos.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)