First-Ever Report Spotlights California, New Jersey, D.C. as Best in Nation for Creating Prenatal-to-3 Policies That Set Children Up to Excel in Early Education

Updated

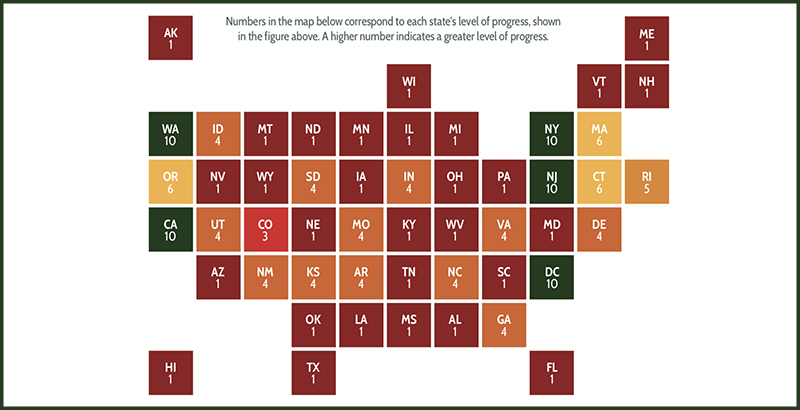

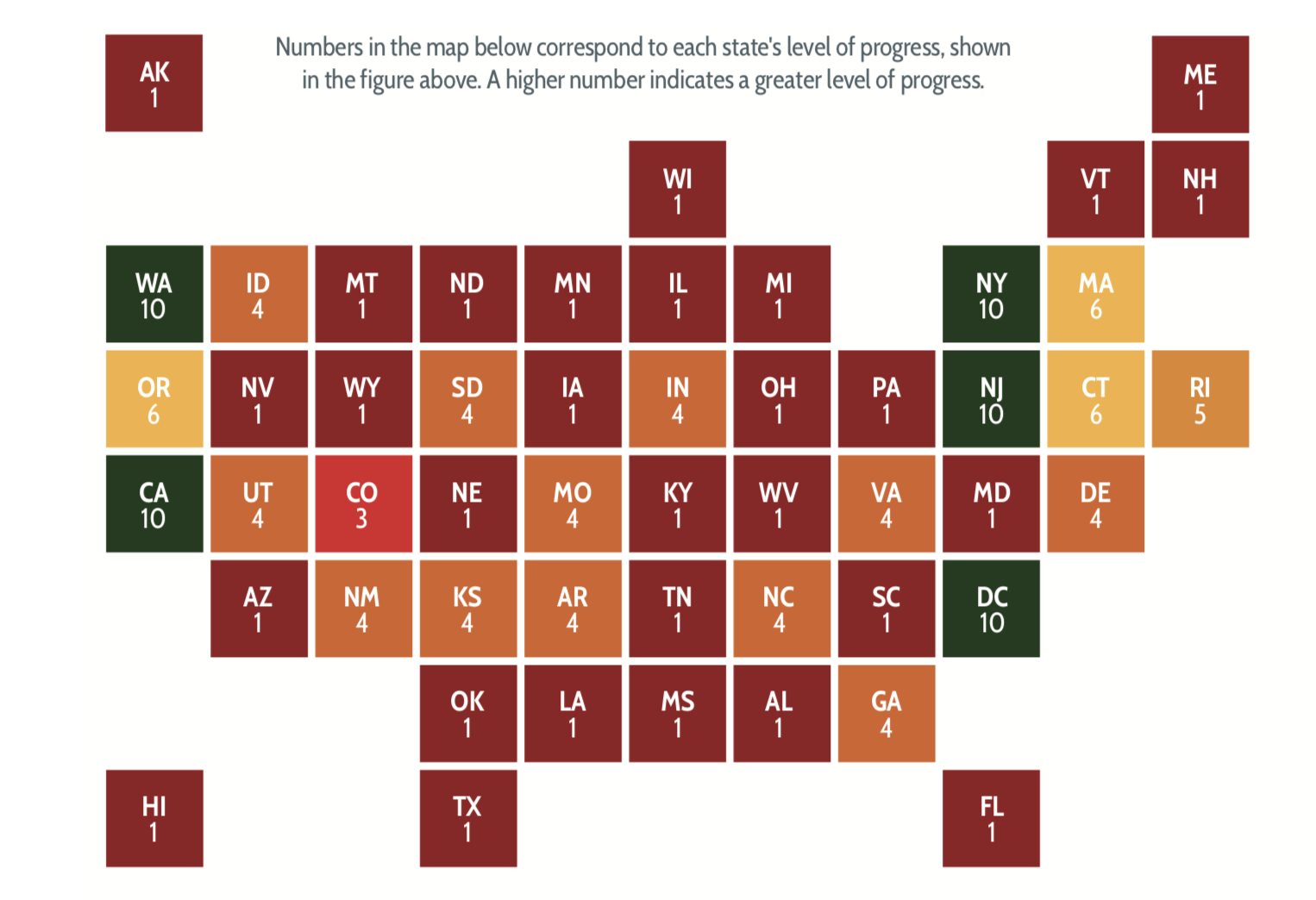

Only California, New Jersey and the District of Columbia have implemented all of the state policies that research shows contribute to young children’s health and well-being during their first three years, according to a comprehensive new “roadmap” released Tuesday.

“The more that kids come [to school] prepared, that sets their trajectory throughout their K-12 experience. That’s one of the reasons why we’ve paid so much attention to pre-K,” said Cynthia Osborne, director of the Prenatal-to-3 Policy Impact Center at the University of Texas at Austin, which published the inaugural report. She added that the new resource will focus on promoting healthy development and nurturing environments before preschool. “It’s a really important age period. It’s the most sensitive to brain development.”

The five state policies highlighted in the roadmap are: expanded income eligibility for health insurance, reduced barriers to applying for food stamps, paid family leave, a minimum wage of at least $10 and a refundable state earned income tax credit that is at least 10 percent of the federal one.

The report, which includes profiles of each state, also recommends six strategies to support young children’s readiness for school, including having a proven screening and referral program, supplementing federal funding for Early Head Start and having broad criteria for which children can access early intervention services. But the findings show that no state has implemented all of them.

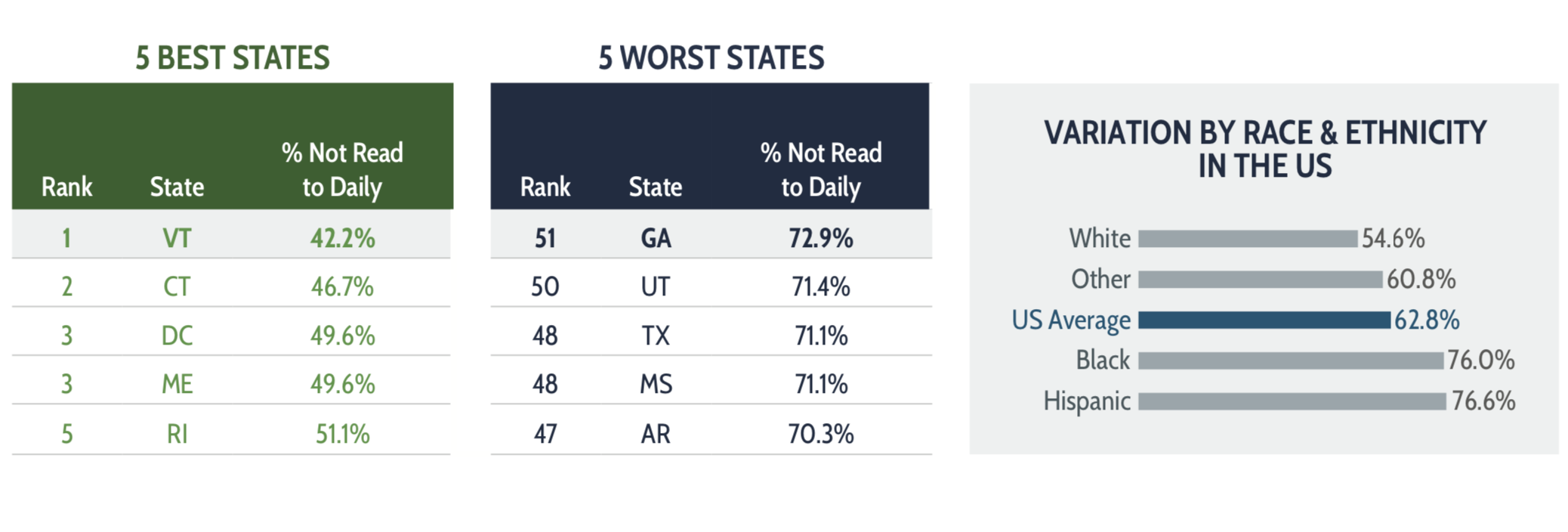

Three states — Florida, Mississippi and Wyoming — haven’t implemented any of the 11 policies or strategies. “That really shows in all of their outcomes,” Osborne said.

For example, more than a third of women of childbearing age in Mississippi don’t have any health insurance coverage, and 2 percent of children under age 3 in the state receive services for developmental delays or special needs, compared with 10 percent in Massachusetts, which has broader criteria for determining which children receive services.

Annual updates of the roadmap will show changes across those 11 areas over time. Osborne added, however, that it’s often difficult to see positive changes over time in states that are larger and have more diverse populations. California, for example, implements the five policies, but outcomes still vary widely. For example, 35 percent of families that have young children live in crowded housing, a rate far higher than in other states. But the percent of children up to age 3 living in poverty — 17.2 percent — is lower than in other states.

‘What families end up getting’

At a time when other research has captured the effects of the pandemic on families with young children, the roadmap is the first to combine what researchers have learned about early development with state-level actions related to infants and toddlers, Osborne said. The document will allow for comparisons between the recommended policies states had in place before COVID-19 and how they responded to the crisis over time.

The policies were chosen because they are supported by research and offer states clear ways to inform legislation or regulations, the report said. Osborne noted that while the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and Medicaid, for example, are federally funded, “state implementation really impacts what families end up getting” because policymakers and officials set criteria for who is eligible for those programs.

Research provides less direction on how lawmakers can implement the six additional strategies, the report says, but they are still considered promising. For example, all states receive federal funding for home-visiting programs targeting low-income or young, first-time mothers. Twenty-three states supplement that funding. But the report notes that the research on benefits is mixed and programs might not be reaching parents and children who need services the most.

Sarah Walzer, CEO of the ParentChild+ program, said that because home-visiting services often have myriad goals and reach different populations, it’s difficult for researchers to find strong outcomes across them. She added that increases in pay and training opportunities for home visitors are policy changes “that could be made to support more consistent outcomes.”

‘Clear policy pathways’

Libby Doggett, who led the Office of Early Learning at the U.S. Department of Education during the Obama administration, said that until now, state leaders have lacked clear direction on which policies help young children thrive before they reach preschool.

“Our very future depends upon children and families with the least opportunity in our country doing better,” she said. “With COVID-19 wreaking havoc on families, it’s more important now than ever for states to have clear policy pathways to strengthen equity and outcomes.”

State early-childhood initiatives for the past two decades have predominantly focused on expanding public preschool, and policymakers have looked to the National Institute for Early Education Research’s annual State of Preschool Yearbook to see how programs compare.

But Osborne said the conditions in which children grow up also deserve attention. “It is important to look in pre-K settings,” she said. “But it’s the things that are happening outside the classrooms that are having as big or bigger an impact.”

The report also highlights some emerging policy areas where states could play a role. One is requiring employers to offer predictable work schedules — an issue that has become especially relevant this year for parents who need to work outside of their home even though child care arrangements might no longer be available.

Future roadmaps will include the return on investment for featured policies. “Lawmakers not only want to know if a policy works,” the report said, “but also how much it costs and how to pay for it.”

Those are the questions that interest Tom Hedrick, who serves on the center’s advisory council and leads a venture capital firm in Austin. Long interested in education issues, he has more recently focused on how businesses can support families with young children — and recruit talent — by offering their employees child care benefits and paid family leave.

“I think we’re at the forefront of solving some business, economic, workforce and maybe some global competitiveness gaps if we do this right,” he said. “If there are issues that start in the upstream, that’s the best place to solve them.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)