‘Are We Being Used as a Test Case?’: Oklahoma Justices Question Catholic Charter

Regardless of the outcome, experts believe the case is headed for the U.S. Supreme Court, which has repeatedly ruled in favor of religious schools.

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

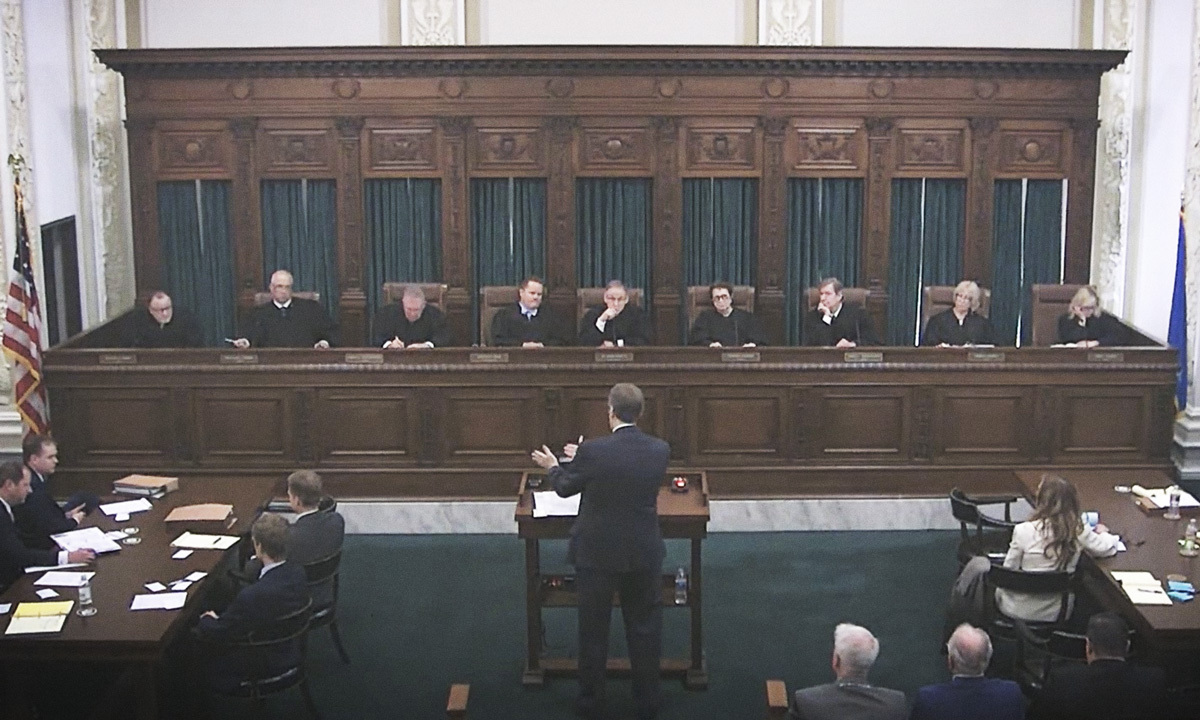

“On July 1, we will violate the law,” Oklahoma Attorney General Gentner Drummond told the state Supreme Court Tuesday, laying out the stakes in a closely watched case that tests the separation of church and state in education.

That’s the date the state will begin to transfer public funds to St. Isidore of Seville Catholic Virtual School to hire teachers, plan curriculum and prepare to open in August. Members of Oklahoma’s Virtual Charter School Board, he said, “betrayed their oath of office” last June when they voted 3-2 to approve a charter with the Catholic church to open the school.

But making arguments that will likely reach the nation’s high court, the attorney for the school said St. Isidore is a private entity and signing a contract with the state did not turn it into a public one.

“St. Isidore was a private organization before it received a charter. The state did not create it,” said Michael McGinley. “It will continue to exist if the state ever terminates the charter. It would have continued to exist if the application had not been granted.”

For nearly two hours, both sides presented very different views of St. Isidore. Attorneys for the charter board and the school portrayed it as a natural outgrowth of a recent “trilogy” of U.S. Supreme Court decisions that favor faith-based schools seeking public funds. But to Drummond — and to advocates for public schools — the case differs from those opinions in that it would not only redefine charters but upset a founding constitutional principle.

On July 1, we will violate the law.

Gentner Drummond, Oklahoma attorney general

“This case is not about exclusion of a religious entity from government aid,” he said. “It is about the state creation of a religious school which unequivocally establishes religion.”

Some of the justices were clearly skeptical of the school’s argument and appeared uncomfortable with the position they found themselves in.

“Are we being used as a test case? Sure looks like it,” said Justice Yvonne Kauger.

And Justice Noma Gurich pushed back on arguments in favor of allowing the school to open.

“Where is the choice for taxpayers in Oklahoma not to support the Catholic Church or the Baptist Church, or the Episcopal Church or the atheist or any other church?” she asked.

What’s clear is that for Oklahomans and the nation more broadly, the case pushes school choice into a new arena.

“I feel that so much is at stake, as a parent, as a taxpayer, but also as an American,” said Erin Brewer, who has two students in the Deer Creek Public Schools, north of Oklahoma City. She’s also a plaintiff in a second case challenging the legality of the school. “We’re talking about the fundamentals of our democracy. We’ve always had the promise that government would never compel religion upon us.”

But Phil Sechler, an attorney with Alliance Defending Freedom, who represents the charter board, said that because families apply to attend, the state isn’t compelling them to do anything. That point echoes arguments made in Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue and Carson v. Makin, two cases in which the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of parents who wanted to use school choice programs to attend parochial schools.

“St. Isidore only gets funds if there is enrollment,” he said. “That breaks the circuit between religion and government.”

One argument against the school has been that if the state allows St. Isidore to open, it would have to approve applications from schools representing other religions. But Sechler dismissed concerns about opening the “floodgates” to Muslim schools, atheist schools and others.

Organizations seeking to open a charter, he said, still have to meet “ample neutral criteria” and provide a quality education that meets a need. For example, they are required to have a financial plan, hire qualified teachers and administer tests.

Oklahoma offers a universal tax credit scholarship that provides up to $7,500 per student for private school tuition, but McGinley said for some families, that program isn’t enough. They can’t afford the rest of the tuition.

“That’s a real hardship for a lot of families,” he said. Charter schools “provide an education where families don’t have to come up with that difference.”

Preston Green, a University of Connecticut education and law professor, called McGinley’s argument a “brilliant framing” that helps the school’s case. He added that if the question eventually reaches the U.S. Supreme Court, he could see the conservative justices siding with the Catholic church.

“It just wouldn’t surprise me,” he said. But he added that the Oklahoma charter case is about more than just religion. It’s also about public education funding. “There’s no real consideration about the impact on the public school system. This could really create some fiscal strain.”

In Black and brown communities, charter schools are very popular, and the concerns about separation of church and state just do not resonate as much.

Preston Green, University of Connecticut

St. Isidore plans to serve 500 students in its first year, and so far, has enrolled or received inquiries about applying from 200 students. Enrollment would increase each year until it reaches 1,500 by the 2028-29 school year.

Green also addressed the question, which Justice Dana Kuehn raised, of whether the state could simply “cure the problem” by not having charter schools at all. Some legal experts have suggested that blue states would be more apt to go that route than to approve religious charters.

But Green thinks that’s far-fetched.

“Charters are such a part of the school environment,” he said. “In Black and brown, especially Black communities, charter schools are very popular, and the concerns about separation of church and state just do not resonate as much.”

While the justices asked a lot of questions about state law and precedent, Nicole Garnett, a University of Notre Dame law professor who was instrumental in preparing the church’s application, said it’s likely the case won’t end in Oklahoma.

“The pivotal issue in their minds appears to be whether St. Isidore’s approval is consistent with Oklahoma law, but they also seemed to understand that the federal constitution must ultimately control the outcome of the case,” she said. “We are hopeful the court will rule soon and allow St. Isidore to begin serving kids in the fall.”

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)