A High School in Ohio Is Giving Students a Choice: Keep Up With Remote Learning — Or You Have to Come Back to the Classroom

Far too many students were skipping online classes and failing this fall at Shaw High School in East Cleveland, one of the poorest districts in the nation and that the state had declared in “academic distress” before the pandemic.

As absences increased through the holiday season, that “academic distress” was only getting worse.

“We saw students struggle in the remote period,” said Henry Pettiegrew, CEO of the district of 1,800 students at Cleveland’s border. “We saw students disengaging. We saw students not logging into classes. We had students and we couldn’t find them.”

So he and Shaw High School Principal Larry Ellis took a bold step. When they opened the district’s only high school to students in January, they took the online learning option away from almost every one of the school’s 600 students and ordered them into the classroom.

“Our students are having a hard time,” Ellis recalled thinking. “Let’s bring them all back.”

Students could only continue online classes only if they had attended 80 percent of their classes and were passing them, a standard only 15 percent of students at Shaw have met. Students also had to agree to a “contract” with the school, that they would keep up with with their lessons.

Click here to see the full COVID Warriors series

That attempt, which has had mixed results, breaks from two national trends during the pandemic – school districts prioritizing a return for the youngest students, and districts letting parents and students pick between in-person or online classes.

More than 500 students at Shaw who didn’t meet that criteria, about 85 percent of the school, all had to return to school in-person two days a week starting Jan. 19.

By mid-February there were encouraging signs and some shortcomings. Attendance at the school still isn’t where officials want it to be. Though Ellis said about 250 students came to school the first week, that has dropped to about 200 now.

“You can mandate that they come, but that doesn’t mean they’re going to walk in the building,” Ellis conceded. “But the push is to have students come in.”

Students who are back at the school say they prefer being in class with their teachers and peers to being at home..

“It’s a lot better,” said senior D’Kano LeFlore. “My grades were terrible online. Now that I’m in person, my grades are getting better.”

Worries about catching COVID at school aren’t keeping D’Kano away, even as the county remains at high risk of spread in both state and national risk ratings.

“I can get sick anywhere,” he said.

Academic and attendance struggles have long been a problem in East Cleveland, a suburb bordering Cleveland suburb that once included the estates of John D. Rockefeller and other early industrialists. But the area has decayed over the decades into one of the poorest in the United States and one repeatedly on the verge of bankruptcy or being merged into Cleveland.

With half of its families living below the poverty level and nearly one in six homes in the city left abandoned and rotting, some estimates have pegged it as the fourth-poorest city in the nation. Stanford University researchers ranked the district 48th-worst out of more than 11,000 districts in the nation, a little worse than Detroit, in a 2016 index of socioeconomic challenges facing students.

With that as a backdrop, the district has repeatedly had some of the worst attendance rates in Ohio and repeatedly scores at or near the bottom on Ohio’s state tests. It was declared to be in academic distress and fell under state oversight in 2018. Then COVID hit and classes were moved online.

“We were behind because of poverty,” said Una Keenon, school board president. “Now we’re even more so.”

“With the pandemic, it’s gone terrible,” she said. “I don’t think half the kids on the computers are going on as they should. They’re not really interested in it. Before it (the weather) became cold, you could see them walking up and down the street during school time.”

As Pettiegrew began planning to open schools in January, he and Ellis decided to prioritize drawing high school students back. He and Ellis said they wanted to make sure high school students pass classes and earn credits toward graduating, a challenge in a district where the graduation rate is just below 80 percent. They also wanted students prepared for college or jobs after high school.

“We just didn’t want kids to be hurt,” Pettiegrew said.

So they decided to give elementary and middle school parents a choice of online or in-person part-time school, but only offer that to high school students with a track record of doing well online. Those students and parents still had to talk with assistant principals and promise to maintain attendance and grades to stay online.

At the same time, the district had three members of its “Graduation Success” team calling, emailing and texting parents of other students to return to school Jan. 19. Thomas Coleman, who heads that team, estimates he also visited 200 student homes between the fall and this winter’s attempts to recruit students back to school.

“A lot of parents are OK with it, but a lot of parents were against it,” he said of the attendance requirement. In many cases, he said, parents are too worried about safety to send students back. Other times, students are working to help support their families and he can’t win them back.

Ellis compared the Jan. 19 opening to the first day of school of a typical year, with students and teachers excited to be back.

“I think they were hungry,” he said. “It wasn’t anything magic we did. They wanted to get back to some sense of normalcy. I think they needed the school as much as the school needed them.”

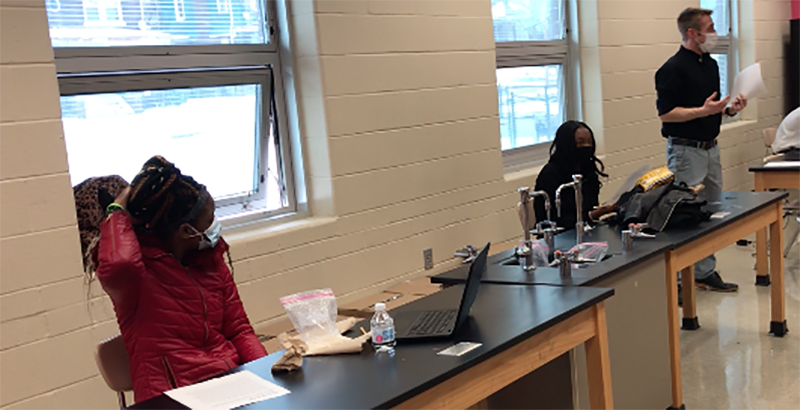

As attendance has dropped and with students split into Monday/Tuesday and Thursday/Friday cohorts, there’s no crowding at the school. A gym class that normally has 50 students had only nine one day recently. A science class had just five students in it, similar to what other teachers say they see in many other classes.

Though low attendance is counter to Pettiegrew and Ellis’ goal, it makes it easy to spread students out for safety. That reassures teachers, who returned to the school before receiving any COVID vaccines and who now have had one of the two recommended doses. The East Cleveland Education Association did not reply to questions from The 74 about the reopening.

“Honestly, i was very worried coming back here,” said music teacher Randy Woods, who has avoided visiting his father who has cancer. “When I started getting five kids in, six on a good day, I said, ‘This I can manage’.”

Woods also said students need a chance to be in school. Some do well online, he said, while others do assignments only sporadically.

“The majority of students benefit from engaging, just being in the space of this building,” he said.

“I think it’s important to give them as many opportunities to be successful as possible.”

Gym teacher Nim Bryant also had worries about returning, but still kept his side job as wrestling coach at East Cleveland’s middle school, which has him on his knees on the wrestling mat up close to kids.

“I have faith,” Bryant said. “I feel like I take as many precautions as you can, but people stayed at home and had everything delivered and still got it.”

Though the full effects of calling so many students back to school will depend on test scores and how many students complete classes, students say coming to school makes it easier to do lessons they might skip at home.

Sophomore Rajahlee Alex said it’s easier to understand classes without lags in WiFi connections and you can interact with a teacher.

“My grades were kind of lagging when we were online,” she said. “’They were pretty bad. It was hard to keep up with it all, but in school, you get it all done here.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)